Early in the war some of the villagers built air raid shelters in their gardens called Anderson shelters, after the man who designed them. These were shed like constructions made of sheets of corrugated metal which were sunk into the ground and then covered with earth to disguise them.

Many people grew their marrows and other vegetables on the Anderson shelter roofs – no space was wasted in wartime – and very successful they proved to be too. Fortunately, these shelters were not needed too often in our neck of the woods, which was just as well as they were damp and, more often than not, after a rainy spell had several inches of water in them.

There was talk at one time of building a large communal shelter on the edge of Sulham Woods but this never materialised. Just as well really, as in the event of an air-raid we would all have had to run up to the shelter via a ploughed field and it was uphill all the way. We didn’t have a shelter in our garden (Father wasn’t going to dig up part of his garden – war or no war). When the siren sounded and the German planes could be heard with their distinctive drone, we would all pile into the big cupboard under the stairs and stay there until the all clear was heard. Normally this cupboard was a glory hole full of junk, i.e. those things we didn’t often use but might come in handy one day. Also, it housed my toys that I would never throw away, so at least it made Mother have a good clear out and she now had space to store all the bottled fruit, jams and other preserves from the garden to supplement our rations during the winter months.

At school we had a very large shelter to accommodate all the classes, and every so often we had to take our lessons there, at first wearing the dreaded gas masks, as part of air-raid practice. It wasn’t very comfortable on hard benches, lit by one dismal electric light bulb.

Once we had a family of hedgehogs resident there and other creepy crawlies as well.

Everyone had to cover their windows at night before you could switch on a light. The covers were made either of thick black material or wooden shutters, and woe betide you if the airraid warden found a chink of light. As he did his rounds, he would shout “Put that light out”, a phrase that was to become very familiar during the war.

As well as food rationing, clothes too were in short supply and so we had clothing coupon books for these as well. The materials were poor and a large item such as a coat, dress or shoes had to be saved for both in money and coupons. Also they had to last a long time, so it was a case of make do and mend. Many mothers would not use their allocation for themselves but save them for their growing families. Shoes were the biggest headache as hems could be let down and seams let out to serve another year then handed on to a younger member of the family, but with shoes it was not so easy as feet came in different widths and lengths. Still, somehow we seemed to overcome these problems. I remember having a pair of wooden clogs, which were not very popular and not comfortable to walk in.

Life did have its lighter side in those war years and one memory I have is the “Home Made Sweet Shop”. It wasn’t really a shop at all as it was in someone’s kitchen. The lady who began this shop during the war lived in an Olde Worlde cottage called Keepers Cottage which is situated between the villages of Sulham and Tidmarsh.

This lady, Mrs David, applied for and obtained a sugar allowance enabling her to make sweets each month. I don’t know how she managed to do this! She made the most delicious sweets, creamy fudge, pink and white coconut ice, satin cushions, twisted raspberry sticks, barley sugar, peanut brittle, all sorts of toffees and chocolates of every type, some decorated with tiny scented sugar violets and many, many more. It must have taken her hours making and filling all the big glass jars, especially as sweets such as barley sugars, satin cushions and raspberry sticks were made in long strips and so had to be cut in smaller pieces at just the correct temperature. If they were cut whilst too warm they would go all squashy, too cold they would shatter all over the place. All this when she was well into her sixties.

The sweets were stored in glass jars and cupboards with tiny drawers and the smell when you entered her kitchen was wonderful and very tempting to us children. She became well known in the area for her homemade sweets and on the first weekend of each month when the new coupons were due, a long queue would form outside her house before she opened in the afternoon. You had to get there early or the best choice would soon be sold out. People came from far and wide for Mrs David’s sweets, some who had been evacuated and then returned to London would come down by train and make it a day’s outing. We were all very sorry when, after the war, she gave it up and moved away.

During the war we were all encouraged to try and save, and to buy National Saving Stamps and this job was taken on by a little lady who was the head mistress’s companion. She came round as regular as clockwork every Monday around 6.30pm and of course we always bought some. I guess it was her part in the war effort.

Many of the larger houses in Tidmarsh such as The Mill, The Grange and The Manor were requisitioned by the military and used as billets for the troops, and of course as mentioned before The Old Rectory housed many baby and toddler evacuees and their mothers.

The soldiers came from various countries at different times. There were our own British “Tommies” of course, Australians, Canadians, and Americans – the G.I.s. Often as I cycled to school in the morning they would be on manoeuvres and both sides of Sulham Lane would be littered with tanks, army lorries, jeeps and all manner of other war time paraphernalia. They set up their camps of tents in a field where they slept over night and would usually be cooking breakfast at that time in the morning, in a make -shift cookhouse. When I came home again in the late afternoon they would all be gone having moved on somewhere else, but most likely by the next week it would happen all over again with another contingent.

Sulham woods and the copse at the back of our house was a favourite place for mock battles to take place. Dummy ammunition was used but this made a very realistic bang and made you jump. The soldiers would come running down from the woods, jump over our garden fence, straight through the vegetable plot, jump the bottom fence, splash through the stream and on into the copse.

I remember one occasion when my Grandmother was hanging out some washing she got very irate with some poor G.I. who did this, waving her fist and telling him in no uncertain terms to stop trampling on our vegetables but all she got was “Sorry Ma’am, but there’s a war on”. I guess in the event of a real battle they wouldn’t have been able to bother about a few old cabbages.

Because of the aerodrome at Theale, some of the airmen stationed there were billeted in Sulham with those families who hadn’t taken in an evacuee. This was sometime around 1942 and as we still had Arnold we were unable to have one. I think my parents would have really preferred to take in an airman and I thought it sounded much more exciting than evacuee. We were all probably getting a bit fed up with him by then.

The airmen were collected in the morning and returned home in the evening in a big R.A.F. lorry which brings to mind another incident of not a very pleasant nature. Just prior to the out break of war, on my ninth birthday, I had been given my first new bicycle. It was lovely and shiny and I was very proud of it. Also too, a bike was very essential to us all as it was our only means of getting anywhere, and in my case, school.

On this occasion during the summer holidays I was doing an errand for a neighbour to fetch a loaf of bread from the bakery at Tidmarsh. It was nearly closing time, so I was pedalling fairly fast. At the top of the lane by Sulham School, I had to cross over and the lane from Tidmarsh was darker with overhanging trees away from the bright sunlight. Suddenly, from nowhere so it seemed, came a big black car and although I tried to turn away it was too late and me, my bicycle and the car collided. It threw me into the air and I landed in front of it with the wheels resting on my back.

I guess I must have nine lives because my only injuries were a grazed knee and hand. I picked myself up and saw the very white faces of two airmen staring at me in amazement, and then rushing out of the house came the school mistress. The airmen promptly picked me up and together with the school mistress took me home. The schoolmistress ran ahead into the house to warn my Mother that I had had a little accident. My Father, coming home from work a little later from the aerodrome, saw my twisted bike in the hedge and recognising it, feared the worst. It turned out, as we heard later, that these two young airmen, one of which whose home was in near-by Tilehurst, were going home for the night. As they didn’t have a pass authorising them to leave the airfield they were driving faster than they should have been to get away before the R.A.F. lorry, which had their sergeant on board, came along and spotted them. As for my poor old bike though, we had it straightened out but it was never quite the same again.

Later on in the war I did have another bicycle as I outgrew that one, but these were like gold dust to get hold of. An uncle somehow managed to get one for me and I suspect it was obtained on the Black Market. The Black Market was illegal trading that went on for things that were difficult to get in the normal way. The source they came from, you didn’t ask and people were only too glad to buy something they hadn’t been able to get for a long time, though prices were high and a lot of profit was made by those doing the selling who were known as spivs.

Anyway, this bike was an adult size and I had to have blocks of wood put on the pedals so that I was able to reach them, but oh dear it was a dreary thing not a patch on my previous one. It was all black, that was the regulations, no chrome bits to be seen whatsoever. Still it was all you could get and it got me from A to B, and, in fact, I had it for many years until things got back to normal and I began work, so I was able to buy another nice new shiny bicycle.

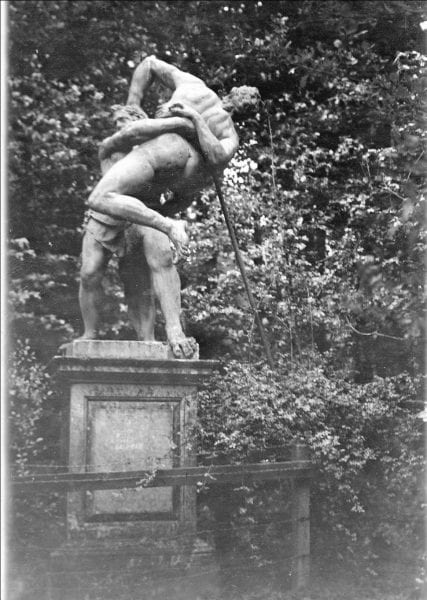

It was during the time we had the air force and military in the area that reminds me of the two large statues. These statues were similar to each other and were of two men wrestling, they were made of lead and stood on a stone base or plinth and were very large figures indeed. One stood in a clearing in Sulham woods above Purley Hall and could be seen from the house and this one had iron railings round it. The other was in a field across the River Pang at Tidmarsh and could be seen from The Grange (since demolished).

One statue was called Cain and Abel and the other The Two Wrestlers, but we were never sure which was which. The one at Tidmarsh became much defaced as the soldiers carved their names and initials in the soft lead. However it disappeared one night, stolen I guess as lead was also valuable. The one at Sulham remained for quite a few more years then that too was stolen and all that remains of it now are some broken parts of the base and a few twisted railings. How these two large figures came to be there in the first place is not clear as they were on separate estates. Maybe they were some sort of status symbol possibly in Edwardian or Victorian times or even earlier.

We were really quite lucky in our neck of the woods compared to some people as far as air raids were concerned. Although the siren went quite often and you could hear bombs dropping in the distance, they usually passed us by. Nearby Pangbourne was lit up one night when they had a heavy raid of incendiaries. However, one evening about 9pm and a very appropriate date – November 5th, (I’m not sure of the year but somewhere around 1942/3) we heard several bombs dropping and they were very close, closer than any we had heard so far. Strangely there had been no air raid warning. My father who was painting the kitchen, jumped, swore as paint went everywhere saying “That was b***** close” and we all dived in the cupboard under the stairs. After a while as nothing appeared to be happening and all was quiet we came out and thought no more of it.

Next day during afternoon school, my Mother appeared at the schoolroom door to take me home. It had been discovered that the bombs we had heard the night before were in fact a stick of seven bombs, and although they were time bombs, some, but not all, had gone off as they hit the trees in the woods. In fact one which had landed in my Father’s allotment had burrowed too far down for the bomb disposal squad to defuse and as far as I know it’s still there to this day.

The police were everywhere stopping anyone who didn’t live in the village from going up the lane. We had to be ready to evacuate so my Mother had packed a suitcase with a few clothes and our rations and we were to go to my aunt who lived along the Tidmarsh Road. As it turned out we didn’t have to in the end as those bombs that hadn’t exploded were buried too deeply for the Bomb Disposal Squad to get to so it was decided to leave them, they were pretty overstretched as it was. Thank goodness that was the closest we got to an air raid, but why on that night Sulham was the chosen target goodness knows. I think the theory was it was a lone bomber maybe on it’s way back from a raid else where, or perhaps the search lights picked him out or he saw a light somewhere and having a few bombs left wanted to get rid of them. We shall never know.