For many family historians the widespread issues with parish registers during the English Civil War (1642-1651) and subsequent Interregnum prove to be an insurmountable brick wall. In this article, Catherine Sampson explores these issues in the context of the parishes mainly in and around Reading, and also highlights a few of the many opportunities within this period.

In some respects Berkshire has fared badly compared to many other counties in the survival of official records for the Civil War period. The Berkshire Quarter Session records were destroyed by fire, few Commonwealth Exchequer papers survive and almost no private letters relating to Reading area families.

The survival of parish registers, the bedrock of most family history research, is varied. Whilst some parish registers are apparently intact, others are largely or partially deficient. The war caused disruption to parish administration and

some registers appear to have been stolen, probably burnt for fuel by the soldiers. Register notes, such as that in St Michael and All Angels, Sunninghill, are reasonably common:

“As for the space of twelve years, viz from 1641 to 1653 there was no care taken for the registring any births, burials or marriages in this parish of Sunninghill by reason of the turmult and confusion of the Civil Warr which has raged in England J.M.”

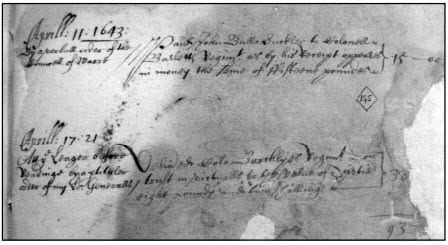

regiments besieging Reading in April 1643 (TNA)

No registers survive for some parishes before 1660. In the extreme, such as at Arborfield, none before the early 1700s, evidencing perhaps the difficulties some parishes encountered in restarting record-keeping even after the Restoration. Purley’s registers only apparently start in 1662, and yet the existence of earlier ones is evidenced by the annual transcripts of it which were sent to the Bishop, which do survive. So accessing original earlier records for these parishes requires a trip down the M4 to the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre where Berkshire’s Bishops Transcripts are held. Even then, you’ll find none survive for Purley between 1638 and 1662.

A further contributing issue was the absenteeism of ministers. Some showed their support too publicly for one side or other, and were obliged to leave the parish for their own safety when opposing soldiers moved in. William Moore followed one such incumbent into Reading St Mary in 1643, after a gap of some months, and found the registers in disarray:

‘ … For people made use of whome they could get to baptize their children; likewise for buryalls without minister, clark, or both, for that no register could be truly kept, but what I could collect or gather together I have done to the uttermost of my power to satisfy peopl[sic]… .’

Moore, like many others, attempted to fill the gaps, but inevitably entries were missed and errors inadvertently introduced. As for marriages, an Anglican service could only be carried out by an ordained minister, and family historians seeking unions during these times may have to cast their net wider. Both Caversham St Peter and Sonning St Andrew experienced significant spikes in marriages in 1643 and 1644, probably partly caused by the on/off absence of ministers in Reading. There is also clear evidence though in both these parishes that some marriages were of soldiers marrying, either local women or an accompanying girlfriend, a pattern probably repeated across the country and worth bearing in mind if you have ‘missing’ marriages from this period.

Churches also became inaccessible to their congregations for periods on end, sometimes because the access routes were unusable, and sometimes because the soldiers were occupying, or had occupied, them. Reading St. Laurence was taken over by soldiers in both 1643 and 1645, preventing services occurring. Whilst William and Alice Jarrat of Sonning, were forced to take their daughter on what would have been a minimum of a four mile round-trip to Caversham to baptise her in 1647, ‘by reason of the troublesome times’. Evidently, Sonning’s church was at that point inaccessible to them for whatever reason. So again, a wide net may be needed to find these entries.

Yet all hope is not lost for family historians with access to unique listings such as the Protestation Returns of 1641–1642. These are lists of English males over the age of 18 who took, or did not take, an oath of allegiance “to live and die for the true Protestant religion, the liberties and rights of subjects and the privilege of Parliaments.” The lists were usually compiled by parish, or township, within hundred, or wapentake and are the closest thing we have to a census for this period. Returns survive for about a third of English counties and can now be viewed online at http://archivesmapsearch.labs.parliament.uk/mapsearch.

Reading’s Corporation records, held in Berkshire Record Office (BRO) are also a much under-utilised resource which survives almost fully intact throughout the Civil War and Commonwealth periods. A tip for anyone planning to consult them – use Guilding’s excellent calendar (available in the society’s reference library and also at the BRO) as a starting point from which to then refer to the original documents. However, also double check the BRO’s extensive catalogue, as Guilding excluded some categories of documents. Reading’s Corporation Archives are catalogued into separate series of documents, of which the most useful to family historians are probably:

| Administration (Military Records) | R/AX series |

| Administration (Petitions to the Mayor) | R/AZ series |

| Financial Records (Constables Accounts) | R/FA13 series |

| Judicial Records (Quarter Sessions) | R/JQ1 series |

| Miscellaneous Documents | R/Z6 series |

| Miscellaneous Records (Civil War) | R/Z10 series |

| Miscellaneous Records (House of Correction) | R/Z8 series |

The information available through these records varies but the following examples give a broad outline of some of what you might expect to find.

- The impact of the war on its traders – mainly contracts awarded, payments demanded, pleas for financial assistance, disputes, and individual cases heard by the Aldermen as they attempted to regulate the Borough market. Examples include: Winifred Sharparow who claimed that she was robbed by soldiers on her way to Newbury Fair, losing goods valued in excess of £200. Whilst Leonard Draper, another trader, was reported for selling earthenware without permission in August 1643 but evidently chose to stay as, a year later, he was fined twice more by the sergeants of mace.

- Reading’s Aldermen and theirBorough service.

- Hospital patients (Reading Greyfriars). Goody Bailey, was admitted on 6 March

1642-3 when she ‘was destracted’ and stayed just over ten weeks, whilst Ann Bennet entered on 24 February 1642-3 and remained until her death on 18 September 1643. - Borough tenancy disputes and pleas for rent leniency. Mary Burnham, for example, petitioned the mayor for relief, probably about 1650, advising that her house had been so ‘ruinated and decayed’ in the war that she had been forced to mortgage it and was now in poverty.

- Borough employees, both permanent and temporary, often concerning non-payment of wages. Thomas Skinner and Nicholas Lamphier successfully petitioned the mayor in December 1644 for payment of their arrears in wages, arguing that the ‘many hindrances of entertaining of soldiers and their attendance and performance of service’ had prevented them attending to their own employment.

- Management of contagious diseases, particularly the plague. For example, in July 1646, Goodwife Lane, sent to examine a stricken child in the house of Robert Bullas, duly reported back that the now deceased child ‘was full of blew spottes’.

- Beneficiaries of Reading’s private charities and almshouses, including the apprenticeship of children, which continued to be administered by the Aldermen throughout the war. Changes in almshouse residency were routinely recorded by the Aldermen including Thomas Cook, a poor labourer, who was awarded a place in one of John A’Larder’s almshouses in July 1643, the same month that Widow Morland won her place in one of St. Mary’s parish almshouses. Cook was dead within four months, Morland within a further two.

Opportunities for profiting from the war were limited for Reading’s craftsmen but some contracts are listed in The Royalist Ordnance Papers, mainly earth-moving equipment as Reading’s defences were constructed, and also iron and steel.

Other trading evidence can be found in the records of the Barge Commissioners at Oxford. Trade there was re-established by at least the end of the war, with one boatman, NicholasHooper of Abingdon, alone responsible for fifty-one boats passing the turnpikes between 28 October 1649 and 3 October 1650.

Finally, family history stalwarts – probate and letters of administration, continue to be important sources throughout this period. However, it is important to note that during the Civil War the church courts were abolished and a single centralised probate system was established – so most wills in Berkshire were proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury rather than by the Berkshire Archdeaconry after circa 1645. Neither were wills restricted to those with considerable estates to leave, the chaotic lines of communication between one town and the next made wills, sometimes, the most enduring means of ensuring a poor widow’s meagre collection of household and personal goods were conveyed after her death to her chosen beneficiary. Likewise, despite, or more likely because, of the war, support for the … (to follow)