Debt has at least as long a history as the concept of money: long before personal banking became the norm, every community has had a few individuals who lent out money to their friends, family and associates.

Evidence of this comes to us from the earliest probate inventories, in which the deceased’s outstanding debits and credits were tallied for settlement.

The Statute of Bankrupts of 1542 was the first piece of English legislation to deal with those who were unable to pay their debts.

Predicated on the widely-held assumption that all debtors were criminal, it talked of those:

“craftily obtaining into their hands great substance of other men’s goods… for their own pleasure and delicate living, against all reason, equity and good conscience…”

Fault lay entirely with the debtor: the law took no account of insolvency which might be due to forces beyond the debtor’s control.

Under the authority of the Lord Chancellor, the debtor’s assets would be seized (in toto), and if he was found to have sheltered anything against seizure, the traditional penalty was the pillory, where his ears would be cut off.

If any debt remained outstanding after distribution, the debtor went to prison, and stayed there at the pleasure of his creditors.

These conditions and attitudes prevailed until the early eighteenth century, when legislation of 1705/06 introduced the novel concept of discharge from bankruptcy, albeit under stringent conditions.

For the first time, a legal distinction was made between the honest and the fraudulent bankrupt.

The former could obtain a release from his unpayable debts, although the latter would face the noose rather than the pillory. In this latter respect, the new legislation was far harsher than the old.

However, the carrot-and-stick policy would seem to have worked, for only four Englishmen were hanged for fraudulent bankruptcy between 1706 and 1820, although some historians believe that weak law enforcement kept the statistics low.

The same legislation allowed for the bankrupt’s wife and children to keep their clothing. One shudders to think of the suffering of families under former insolvency practices.

A distinction arose also between bankrupts and insolvent debtors. To benefit from the new legislation, i.e., to go bankrupt, one had to be a trader, making one’s living by buying and selling. Farmers were specifically excluded.

Those struggling to meet the criteria usually described themselves as “dealer and chapman” as a legal convenience, and in bankruptcy records this phrase is no true guide to an individual’s occupation.

Those who did not meet the criteria were mere insolvent debtors, and went to the debtors’ prison as of old.

Around 10,000 were imprisoned annually for debt during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. London had nine debtors’ prisons of which, thanks to Charles Dickens, the Marshalsea is probably the best known: his father was sent there, inspiring the story of Little Dorrit, whose father’s debts were so complicated that he faced a lifetime of incarceration.

Inmates would not be released until they had paid their debts in full and, furthermore, they had to pay for their own keep. Support from friends bringing in food, small comforts and money to bribe the gaolers was essential for survival.

The misery surrounding insolvency has handed a few phrases down to us: in the Clink refers to another of London’s debt prisons; stoney broke also comes from the Clink, with its debtors’ entrance on Stoney Street; and lastly, the slightly lesser-used phrase on Carey Street, a euphemism for financial embarrassment, originates from the London street to which the UK bankruptcy court moved in the 1840s.

Nineteenth-century legislation encouraged the formation of corporate trading bodies and gradually loosened the bonds of bankruptcy and insolvency, in recognition that a healthy economy needed entrepreneurs who should not fear going into business.

Those who made honest mistakes should get a second chance to prove themselves productive citizens.

Key dates to be aware of include:

- TheDebtors (England) Act of 1813 established the Court for Release of Insolvent Debtors through which gaoled debtors could ask for release after 14 days by taking an oath that their assets did not exceed £20, provided none of their creditors objected

- The Bankrupts (England) Act1825 allowed debtors to apply for their own bankruptcy (with the agreement of their creditors). Hitherto, only creditors could start the proceedings

- In 1832 the Court of Bankruptcy was established, taking matters out of the hands of the Court of Chancery. Ten years later district bankruptcy courts were set up for cases outside London

- From 1844 companies, rather than just individuals, could use the process, reflecting changing attitudes to commercial corporations

- From 1861 insolvent debtors could apply for bankruptcy even if they were not traders. The Debtors Act of 1869 reduced the circumstances under which debtors could be sent to prison. Some sources describe it as the end of imprisonment for debt, although at least one historian quotes the figure of 9,759 gaoled in 1869 plummeting to 6,605 the following year, yet by 1905 the figure was 11,427.

So where might a family historian find information on an insolvent ancestor?

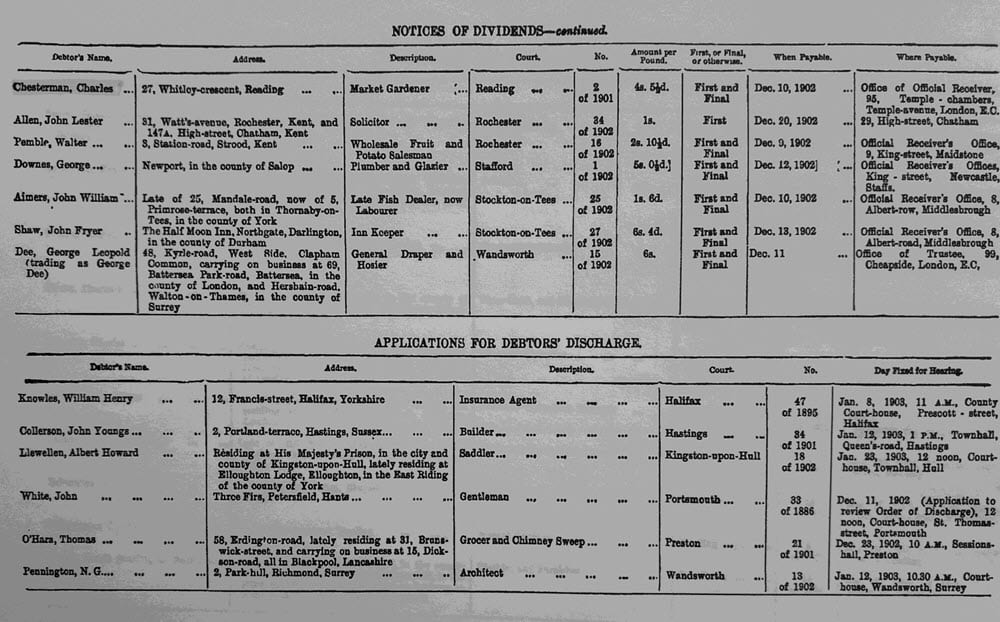

From the early 1700s all bankruptcy proceedings were announced in The London Gazette, the first official newspaper of record.

Announcements invited creditors to submit their claims to the receiver at an appointed time and place, often a reputable local inn.

The entire archive can be searched for free on https://www.thegazette.co.uk. However, the Gazette doesn’t always tell you what happened next.

Having found your impecunious ancestor in The London Gazette, you will know his name, date, location and possibly his trade. Then visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/bankrupts-insolvent-debtors to explore your specific case.

TNA holds a vast and complex archive of insolvency records, all admirably explained here.

Article Sources

Wikipedia on: Debtors’ prisons; History of bankruptcy law; UK insolvency law; and the individually named Acts.

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/bankrupts-insolvent-debtors/

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/all-notices/content/100938

Emily Kadens. The last bankrupt hanged: balancing incentives in the development of bankruptcy law (Duke Law Journal, v59, April 2010 m no 7)

Ann Carlos et al. Conformity and the certificate of discharge: bankruptcy in early eighteenth century England (Colorado University, 2010)