Whilst the physicians and surgeons of Georgian times were technically regulated by their respective professional bodies, standards of training and practice were unenforceable. The majority of country practitioners were wholly uneducated and often plied surgery alongside other random trades such as ironmongery or shoemaking.

Whilst the physicians and surgeons of Georgian times were technically regulated by their respective professional bodies, standards of training and practice were unenforceable. The majority of country practitioners were wholly uneducated and often plied surgery alongside other random trades such as ironmongery or shoemaking.Genuine physicians, according to the royal college, obtained their MD qualification at one of England’s two (or Scotland’s three) universities, although the syllabus involved more classics than science. Physicians specialised in internal diseases, treating mainly the upper classes, for whom they prescribed in Latin. The gold standard was membership of the Royal College of Physicians, but not many MDs attained this.

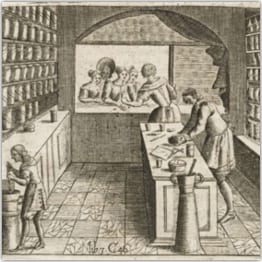

Surgeons qualified by means of apprenticeship at London hospitals, followed by an oral exam at the College of Surgeons. Apothecaries were also licensed by statute, and over the eighteenth century, joined forces with the surgeons, giving rise to the surgeon-apothecary, forerunner of today’s GP.

Male practitioners shunned childbirth until the introduction of forceps, whereupon it became fashionable to call the man-midwife.

Women, who had enjoyed professional status as surgeonesses in the seventeenth century, fell from favour during the eighteenth, possibly because of the male-dominated colleges. However many widows of unqualified country practitioners continued to run the family business after their husband’s death.

Quackery abounded. Unqualified itinerant “doctors” moved from town to town, dispensing miracle cures for all diseases. Operating from hired rooms for a day or two, they left before their charlatanry could be denounced.

A professional consultation could cost a month’s wage for a labourer, so poorer people relied upon the church overseers, charities and friendly societies for (exceedingly patchy) provision of medical services. A free dispensary existed in Newbury briefly from 1778-83, and was revived in 1835, but applied stringent entry criteria.

Newbury usually had a couple of MDs and perhaps three or four surgeons at any given time during the Georgian era, with slightly more provision in the early nineteenth century, when some surgeons also gained MDs. Whilst Newbury physicians often came in from outside and practised alone, surgeons tended to come from local families in which the profession was a tradition. They also often practised in partnerships.

Three Newbury practitioners have left behind letters and other records which have granted insight into their private and professional lives: John Collet MD MRCP, Robert Scott MD and William Savory (surgeon).

Cause of death was never systematically recorded; it appears only spasmodically in burial registers, usually as a description of symptoms rather than a specific disease. Smallpox was the exception, being a major preoccupation to the extent that even the corporation became involved in epidemics. Newbury had outbreaks throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the worst being in 1767-68. The corporation and vestry followed two policies: mass inoculation (which carried severe hazards until Jenner’s vaccination was developed) and the isolation of patients in pest houses. Neither was particularly effective. Fear of infection caused widespread fear of strangers, including the army units regularly billeted in the town. Measles was second to smallpox in its likelihood of mention in registers. TB was particularly rife in the eighteenth century. Puerperal fever killed many newly delivered mothers. Syphilis affected both sexes widely, was poorly understood (confused with gonorrhoea) and never recorded by name. Cholera arrived in England in 1831, giving rise to a major panic, although Newbury’s first major epidemic was not until 1849. Accidents (drowning and horse-related) despatched a significant number of townspeople. Suicide was beginning to be recognised as a form of temporary insanity, no longer precluding Christian burial. Traditional treatments were at best ineffective and at worst lethal: purging, bleeding and cupping were applied liberally, laudanum was routinely given to infants and mercury was the standard remedy for venereal diseases. At a less violent level, herbs and asses milk were favoured, but many treatments were based on ancient superstition.

A vast range of patent medicines was available from local shops (often booksellers), promising relief from myriad complaints. Some were patented, and all came with emphatic testimonials. There was much detail on the many ills of male sexuality, but “women’s troubles” were treated as an undifferentiated mass. For the underclass who could not a few shillings for a bottle of magic syrup, there remained recourse to age-old folk practice and old wives tales. Witchcraft was still practised, and strands of it still permeated even the highest professional medical thinking. Whilst it is generally agreed that life expectancy improved over the eighteenth century thanks to general prosperity and better nutrition, the reality was that professional medical attention was as likely to kill as to cure.