Born in Stockport to a Salford mother and a father from a London family, I had no idea of having Berkshire ancestors as I got interested in my family tree. Our only connection with Berkshire was my father’s sister Pat, who trained as a nursery nurse in Reading in the 1950s. Pat returned to the area to help out with running Romans Hotel in Silchester in the early 1960s, and settled as housekeeper at ‘The Croft’ in Padworth in 1970 after marriage, while her husband got a job as a painter and decorator at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment in Aldermaston.

We started our research in 1980, when my sister was studying in London. Record-searching was a complicated business way back then. We haunted St Catherine’s House to search the indexes to civil registration of births, marriages and deaths, and made visits to Portugal Street to consult the census returns on microfilm. The release of the 1881 returns was an exciting development, and we discovered that the father of my father’s paternal grandmother claimed to have been born in Berkshire, without specifying where. But trawling back to the 1871 returns, we were rewarded with more detail – his place of birth was Padworth! Auntie Pat had settled in a tiny village which turned out to have been the residence of her ancestors, and as our research progressed we found that the family, the Sopers, were blacksmiths in the village for 150 years and more. They also provided blacksmiths to several other Berkshire villages.

There is a beautiful double headstone on a grave near the Padworth church door, which commemorates John Soper and his wife Ann, the first Sopers to appear in the parish records. Above the inscription to John is a carving of a shield with a design of three horseshoes, which may indicate that he was a member of the Worshipful Company of Farriers, although we have found no evidence to prove that.

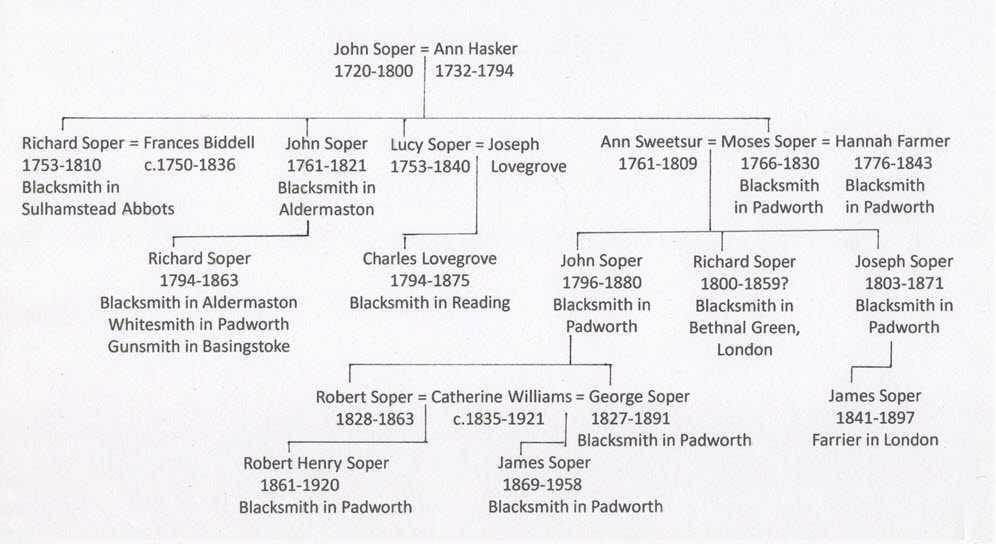

John and Ann baptised ten children between 1753 and 1772. The eldest son, Richard, became blacksmith at Sulhamstead Abbots, probably after his marriage in 1791 to Frances Biddell. Another son, John (my ancestor, who we could call ‘John II’), became blacksmith at Aldermaston and appears to have inherited the Sulhamstead smithy on Richard’s death in 1810, subject to Frances’ life interest. Richard and Frances had no children, but Frances outlived John II by 26 years and left the smithy to her nephew Richard Biddell – I’m not sure whether that was entirely legal! However, John II’s descendants had no need for a smithy, having made good as whitesmiths, ironmongers and gun-makers in Reading and Basingstoke.

John and Ann’s eldest daughter, Lucy, married Joseph Lovegrove from nearby Ufton Nervet, who may himself have been a blacksmith but cannot be traced. Their son, Charles, was a blacksmith in Reading, and his son, Joseph, is described as a ‘smith’ on the 1851 census record, but is found in later census returns in London, as a maker of artificial teeth (a ‘mechanical dentist’ as he is described on his son’s marriage certificate).

It was the youngest son of John and Ann, Moses, who succeeded his father as blacksmith of Padworth, and his sons and grandsons provided blacksmithing services in the village into the 20th century. Moses would have come of age in 1787, and we assume that he worked alongside his father. In 1800 he witnessed the ‘administration’ of his father’s property after John II’s death without a will. Two of his sons by his first marriage, John III and Joseph, became blacksmiths in Padworth (coming of age in 1817 and 1824 respectively). Again, we assume they worked alongside their father.

Moses died in 1830. He had married his second wife, Hannah Farmer, in London in 1811, and in his will left his blacksmith’s business and goods to ‘my dear beloved wife’ for life, ‘and at her death I wish all to be equally divided amongst my children, likewise I wish that any of my children may have a home that requires it’. This last proviso seems an odd one. He and his first wife had had seven children, but by 1830 the eldest son was married, the youngest was dead and two others had moved into London, as had the two daughters. The Padworth poor rate records show Hannah running the business in the 1830s and 1840s. In the assessment of 19 May 1838, she is the occupier of a house, smith’s shop and land ‘near Old Farm’, owned by Richard Benyon, Esq, totalling 8 acres, with a rental value of £14 and rateable value of £11 14s. She paid eight shillings, ninepence halfpenny towards the parish poor relief. Her name is followed in the record of February 1843 by that of her step-son John III, who in the next available volume (1847) is running the business himself.

Hannah was recorded in the 1841 census returns as ‘smith’ in the village. John III and Joseph were also recorded as smiths, but were claiming poor relief in the 1830s and 1840s. John III is recorded as occupying a cottage and garden at ‘Priors’ (listed between properties near the Parsonage and properties near Hatch Farm), for which he was liable to pay 1 shilling towards the poor rate, but he was excused ‘on account of … poverty and inability to pay’. I am intrigued – was Hannah a ‘wicked step-mother’ keeping all the profits of the business to herself, or was it just ‘benefits fraud’? When Hannah was buried in Padworth in 1843, she was described as a resident of Reading (which is where her daughters were married in 1833 and 1836 respectively).

John III is listed as Parish Clerk in Kelly’s Directory of 1848. The Padworth vestry minutes in 1853 record that it was agreed to put in nominations for John III and Joseph Soper to serve as constables for the parish, and John III Soper (with Edward Perkins) was appointed surveyor of the highways. The Churchwardens’ accounts record frequent payments to John III Soper between 1844 and 1875, including for ‘iron work etc’ in 1865. From 1850 he was paid annually for repairing and cleaning the stove [in the church]. John III died in 1880. Joseph is recorded in the censuses of 1851 and 1861 as ‘blacksmith’ but is ‘Parish clerk’ in the 1871 returns. He died in October of that year.

The other surviving sons of Moses were Richard (b.1800) who is recorded in the 1851 census returns as a blacksmith in Bethnal Green in east London, and Moses II (b.1801) who is also found in London in the 1851 census returns, but as a butler in a house in Piccadilly. He appears to have then married into a bakery business, and is found in 1861 as a grocer and baker in Amesbury, Wiltshire.

John III had three sons. The youngest, Charles, became a carpenter and settled in Reading. The second, Robert, went to London and is recorded as a servant on his marriage in 1858. The eldest, George, is recorded in his father’s household in the 1851 returns as a blacksmith, but he then also left the village. He married in 1854 in Oxford and can be found in the 1861 returns as a labourer in Abingdon, at that time Berkshire’s county town. Three children are known to have been born to George and his wife, Sophia, but Sophia died in 1863. It seems their younger son also died – a William Soper aged 4 was buried at Padworth in April 1864.

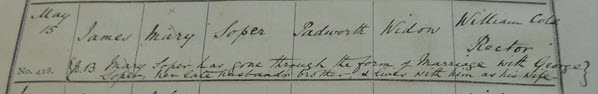

In September 1864, George married Catherine Soper, the widow of his brother Robert (who had also died in 1863). Such a marriage was illegal before the Deceased Brother’s Widow’s Marriage Act of 1921, and some disapproval can be discerned as they returned to Padworth. Catherine had two sons, Robert Henry Soper from her first marriage and Charles Griffiths Soper from her ‘marriage’ to George, and the record of the baptism of a further child at Padworth parish church reads (confusingly mistaking the mother’s name): ‘James, son of Mary Soper, widow, 15th May 1870. N.b. Mary Soper has gone

through the form of marriage with George Soper, her late husband’s brother, & lives with him as his wife’. Catherine Soper has been entered here in error as ‘Mary’, the name by which she had been known in service. They had married in Oxford Registry Office. It appears that George’s surviving children from his first marriage were left with their grandparents in Oxford. The boy, John Tubb Soper, became a Bath chairman in the city.

George is recorded as a blacksmith in Padworth in the 1871 and 1881 census returns, and like his father, he undertook work for the parish churchwardens – he is recorded in their accounts up to 1890. He died in February 1891. Catherine survived him by 30 years, and was a notable figure in the village, undertaking charitable work such as arranging for disadvantaged London children to stay in local cottages on behalf of the Children’s Country Holiday Fund. The Reading Mercury of 23 July 1898 bears a small article:

‘London Children’s Summer Holidays.

A Correspondent writes “Far away from the smoky, dusty city, Padworth is a charming place, with its open common and lovely pine woods, for the London children to spend a few weeks in the summer, where they can roam about and enjoy the country to their hearts’ content; and it is a happy time for the children when they do come down, under the motherly care of Mrs Soper. Recently a large number of the Stepney holiday children had a delightfully happy day at Arlington Manor near Newbury, whither they were conveyed in vans, under Mrs Soper’s charge, and where they were kindly received and entertained by Major W. Evans Gordon and the Marchioness of Tweeddale, and where all spent a very pleasant day’

When Catherine died in 1921, she was buried (I assume at her request) with Robert, her first husband. The marble tablet marking their grave is now missing, but fortunately a graveyard survey was made in 1942 which records the inscription.

Joseph, the second son of Moses I had five sons, four of whom survived to adulthood, but only one went into the smithing trade. The eldest, Richard, became a servant and is recorded as a butler in Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire. His four sons became respectively a railway telegraph clerk in South Wales, a legal clerk in Bedford, a steward on board ships, and the landlord of the Ormond’s Head Hotel in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Joseph’s second son, John, became a bricklayer and is recorded in his parents’ household in the census returns of 1851 and 1861, and in his elder brother’s household in Minchinhampton in 1871. The third son, James, is recorded as a ‘farrier’ in the record of his marriage in 1872, and appears to have worked for a railway company. He may be the ‘railway servant’ found in Paddington in the 1871 census returns and the ‘railway porter’ in Greenham, Berkshire, in the 1881 returns. Sadly, his wife appears to have died giving birth to their second child, and their older child, another James, was brought up in Padworth by a widowed aunt, Mary Ann Rye. The last surviving son of Joseph, another George, worked all his life in London as a warehouseman in the fur trade and also suffered the early loss of his first wife. He retired to Padworth, and in 1904 at the age of 60 married Louisa Devonish, widow of the former Padworth House coachman, James Devonish (who had been recorded in the 1901 census, shortly before his death, as a corn merchant).

The blacksmith’s forge at Old Farm (at the top of Silver Hill, now Silver Lane) was still manned by a Soper as the twentieth century dawned. Catherine’s eldest son Robert Henry Soper is recorded in the 1891 census returns as blacksmith at Silver Hill, and that may also have been his residence in 1901, although at the time of the census he was living with his mother while his wife was in hospital. Catherine and George seem to have moved from the ‘Old Farm’ location given in the census returns of 1871 and 1881 to a house on Ufton Road (now Baughurst Road). George’s address is given as ‘Round Oak’ on registers of electors, 1885-1890, and Catherine is recorded as a widow living ‘near Round Oak’ in 1891. The 1911 returns give her address as ‘Sunnyside’, and her son James is recorded at that address in the 1939 Register of England and Wales and in the record of his burial in 1958. They probably occupied the house at Sunnyside Farm, which is directly opposite the old Round Oak Inn.

Sadly, Robert Henry is recorded in the 1911 census as a ‘lunatic’ in the Berkshire Asylum and he died there in 1920. He had two sons: Frederick, who became a carpenter, and Maurice, who became a butcher (as recorded in the 1911 census). Both served in the army in WW1 and were poisoned in a gas attack on the Western Front. Maurice died in 1919 and is recorded on the village war memorial, but Frederick lingered on until 1926, too late to be counted as a war death.

Of Robert Henry’s half-brothers, Charles Griffiths did not follow the family trade, but worked more closely with horses: the 1891 census returns record him as a groom at Beenham House, and the 1911 returns as a ‘Coachman – Domestic’ (but he is described as a ‘Laundryman’ in the record of his marriage in 1901). James, whose baptism record back in 1870 (above) showed the disapproval of the officiating clergyman to his parents’ marriage, was recorded in 1891 and 1901 as a blacksmith, living in his mother’s household at ‘Round Oak’, but by 1911 he was a cattle dealer.

In the 1911 census returns, the only blacksmiths in Padworth or Ufton are not Sopers. The smithy at Padworth is occupied by Arthur Hearn, born in Woolhampton, with wife Jane, born in Aldermaston, with their four sons (the eldest also a blacksmith) and a daughter.

Many branches of my family tree seem to start with somebody called John appearing in a parish where he has no apparent connections. Where the original John Soper came from is a mystery. It is possible that he was descended from the Sopers of Hannington and North Oakley in Hampshire, although they appear to be minor gentry. According to a Soper family tree, a Richard Soper of North Oakley, who died in 1655, had four sons, only one of whose descendants are recorded. However, attempts to trace any descendants of the other sons have failed: North Oakley is not itself a parish, the parish registers of Oakley do not feature any Sopers in the 17th century, and the parish registers of Hannington (and the Bishop’s Transcripts thereof) have not survived before the 18th century. The youngest of the four sons, another Richard, left a will naming 8 children, but died so young (in 1675) that none of them was yet 21 years old, let alone married. So I have reached a dead end – but it has been tremendously interesting to see the contributions which the Sopers made to a village which I used to visit in my childhood.

With many thanks to all the Soper descendants whose researches have added to my knowledge of the family, especially Nigel Soper, Clive Soper, Janet Dormer, Judith Dyer and Pam Raven, and to Brian Wilcock for drawing my attention to the 1942 graveyard survey.