My great-great-great-great-grandmother, Ann Davenport (or Devenport) (c.1753–1828), served in the royal household of George III, at Windsor, for many years. She was employed initially as “Necessary Woman” to the Princesses and is later described in Queen Charlotte’s account book as “Housekeeper at Lower Lodge”, Windsor. It seems likely that her husband was Thomas Davenport (or Devenport), Assistant to the Queen’s Pages from c.1777–c.1801, when he probably died.

Ann (right, in an oil painting from 1790) and Thomas had four children, William (died after 1818), Martha Caroline (1785–1811) and my great-great-great-grandmother, (Georgiana) Sophia Goertz (née Davenport) (1788–1818). However, a bizarre, and very sad, event concerns the 4th child, a girl whose names and age are not known. It is vividly described in a number of contemporary journals, including The London Chronicle, The Literary Panorama, The London Annual Register and the splendidly named Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, and is also referred to in a letter to the Prince Regent dated 10th August 1813 from the Queen of Württemberg.

The report in the Edinburgh Annual Register for 1813 is typical of the way in which the strange incident is related. It reports that, on 2nd May:

![Queen Charlotte (1744 - 1818) by Thomas Gainsborough [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://berksfhs.org/wp-content/uploads/2025-02-11_21-15-59.png)

The prince regent received an account from Windsor, of the queen’s being indisposed, in consequence of an attack from a female domestic, who was seized with a violent fit of insanity. The prince ordered a special messenger to be sent to Windsor, to enquire after the health of his royal mother, and the full particulars of the attack. On the return of the messenger the prince sent off Sir Henry Halford, at seven o’clock in the evening, to attend her majesty. The circumstances of the attack are stated as follows:-

The unfortunate female who caused the alarm is named Davenport, and held the situation of assistant mistress of the wardrobe to Miss Rice. Her mother has been employed a number of years about the royal family; she was originally engaged as a rocker to the princesses; and after filling a variety of situations very respectably, until she has attained the high office of being housekeeper at the Lower Lodge, Windsor. Her daughter, the subject of this article, was born in the queen’s palace; she is now upwards of 30 years of age, and has lived constantly with her mother, under the royal protection.

When she was a girl, she was attacked with a fit of insanity, but was considered perfectly cured; however, she has frequently been seized with fits of melancholy, crying and being very desponding, without any known cause. Her mind had

![Princess Amelia (1783 - 1810) after William Beechey [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://berksfhs.org/wp-content/uploads/2025-02-11_21-24-21.png)

been more affected since the death of the Princess Amelia. She was present at the delivery of the funeral sermon which was preached at Windsor on the melancholy occasion, and which had such an effect on her mind, that she became enamoured of the clergyman who delivered it, and report assigns love to be the cause of the violent mental derangement with which she was seized on Sunday morning.

She slept in the tower over the queen’s bed-room. About 5 o’clock her majesty was awakened by a violent noise at her bed-room door, accompanied with a voice calling loudly for the queen of England to redress her wrongs, and with the most distressing shrieks and screams imaginable. The queen’s bed-room has two doors; she used such violence as to break open the outer door, but found herself unable to break the inner one.

Mrs Beckendorf, the queen’s dresser, sleeps in the room with her majesty. They were both extremely alarmed, particularly at first. Her majesty and Mrs Beckendorf hesitated for some time about what had best be done; when having ascertained that it was a female voice, Mrs Beckendorf ventured to open the inner door and go out. She there found Miss Davenport, with only her bodylinen on. She was extremely violent with Mrs. B., insisting upon forcing her way into the queen; and the latter feared that, could she have obtained her object of getting into the queen’s bed-room, she would have vented her rage upon her majesty, from the language she used.

She had a letter in her hand, which she insisted on delivering to the queen. Mrs Beckendorf was placed in a most perilous situation for about half an hour, being subject to her violence and endeavouring to prevent her from forcing her way in to the queen; and during this time the queen heard all that was passing, and was in great agitation and distress, lest Miss Davenport should gain admittance to her; the unfortunate female declaring the queen could and should redress her wrongs. Mrs Beckendorf in the mean time kept ringing a bell in the passage, but unfortunately did not at first awake any one, though at last the incessant and violent ringing of it awoke Mr Grobecker, the queen’s page, and two footmen, who came to Mrs Beckendorf’s assistance.

Miss Davenport made use of very profane language to Mr Grobecker. All these persons could not manage her till Mr Meyer, the porter, came, and he being a very powerful man, accomplished it. When she found herself overpowered, she insisted on seeing the king, if she could not see the queen. Mr Meyer carried her by force up to her bed-room, laid her on her bed, and covered her with some clothes, but she kicked them all off. Dr Willis1 was sent for, who ordered her a strait waistcoat; and she was sent off in a post-chaise, accompanied by two keepers, to a house at Hoxton2 for the reception of insane persons.

In her book Princesses – the Six Daughters of George III (pub. John Murray, 2004), the historian Flora Fraser describes the reaction of Princess Augusta to this alarming event:

![Sir Henry Halford (1766 - 1844) from medical portrait gallery

[public domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://berksfhs.org/wp-content/uploads/2025-02-11_21-29-25.png)

[public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Princess Augusta wrote to Sir Henry Halford (physician to several members of the Royal family) from Windsor on 2 May 1813: ‘The chambermaid Davenport (who has been very strange for a long time past) went raving mad in the night and at five this morning she flew down to the Queen’s door.’ Davenport knocked and called out to Mrs Beckedorff (sic) who went out to her. Davenport declared she would see the Queen, and Princess Augusta too. Upon Mrs Beckedorff telling her ‘in her mild way’ that she would not wake the Queen but that she should see her in the morning, the chambermaid ‘threw herself on the floor and swore and screamed in the most violent manner.’

The matter passed out of the royal ladies’ hands when Dr Willis’s men, hastily summoned from across the quadrangle, placed the girl under restraint. ‘In that state’, wrote Augusta with horror, she was now – ‘thank God’ – gone to London. And, Dr Millman, for whom her mother had an ‘adoration’, not being available, Dr Baillie came to quiet the Queen.

The reports suggest that the unfortunate Miss Davenport, who had clearly suffered from mental problems since childhood, had been greatly affected by the funeral of Princess Amelia, a “beautiful and slender girl with ruby lips and auburn hair” and “amiable, spirited, unselfish and intelligent”, who had died in 1810, having suffered from ill health for several years. The Princess’s funeral, as was royal custom, took place in the evening of 13th November. A contemporary account described the ceremony. In the “Grand Procession” to the Chapel Royal, the hearse was followed by two royal carriages containing attendants of the late Princess, including Mrs. Davenport. Behind them came the carriages of the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge. (Both Princess Amelia and the Duke of Cambridge were godparents to two of Sophia’s children, who were named after their royal sponsors.)

Once inside the Chapel, the funeral procession made its way up the aisle, Ann Davenport taking her place with the “Ladies attendant on Her Majesty and the Princesses”, led by Lady Albinia Cumberland and including “Madame” Beckendorff. The latter, who was German, was Mistress of the Wardrobe, a close companion to the Queen and a friend of Sophia’s family, as is evident in letters exchanged between Sophia and her husband Heinrich Goertz while the latter was on a mission for the Queen in Hanover. (Eight years later, Mrs. Beckendorff would hold Queen Charlotte in her arms for long hours during the Queen’s last illness.) Ann’s daughter (her name is not known) took her position in the rearmost group, consisting of the Queen’s and Princesses’ dressers. The emotion of the occasion, at the late evening hour, in darkest autumn, clearly affected the girl deeply, not to mention her developing a “crush” on the officiant!

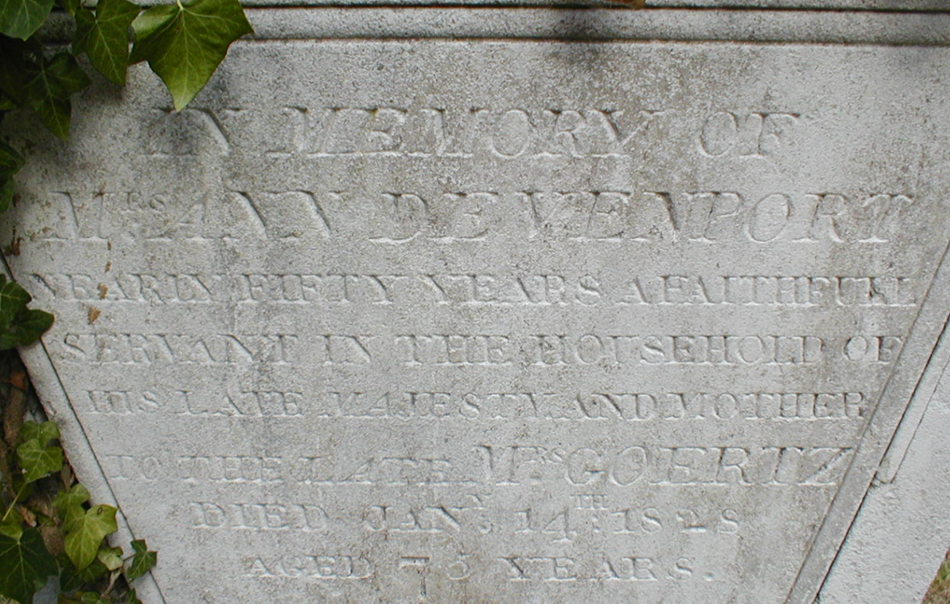

It is not known what became of the poor young woman following her fit of insanity. In the early 19th century, “lunaticks” were beginning to be treated with more compassion than in previous ages, but there was no treatment and “the house at Hoxton” gained an unfavourable reputation owing to its lack of care for its inmates. We must assume that my unfortunate great-great-great-great-aunt died in the madhouse. Fortunately, this episode did not dampen the Queen’s affection for Ann and her son-in-law Heinrich. After a lifetime’s service in the household, the old lady, who had sadly outlived Sophia, retired in 1819 in receipt of a royal pension of £215 p.a. and died in 1828 aged 75. Her headstone in Old Windsor churchyard, using the alternative spelling of her surname, bears the inscription: “IN MEMORY OF/ANN DEVENPORT/NEARLY FIFTY YEARS A FAITHFUL/ SERVANT IN THE HOUSEHOLD OF/HIS LATE MAJESTY, AND MOTHER/TO THE LATE MRS GOERTZ/DIED JANY 14TH 1828/AGED 75 YEARS”.

Endnotes

- This would have been one of the two sons of the famous alienist, Dr. Francis Willis, who through his revolutionary treatments had apparently “cured” George III – at least temporarily – of the monarch’s earlier bout of insanity. After Willis’ death in 1807, his physician sons continued to minister to the King.

- Hoxton House was a lunatic asylum that achieved notoriety through its scandalously neglectful and sometimes cruel treatment of its inmates.