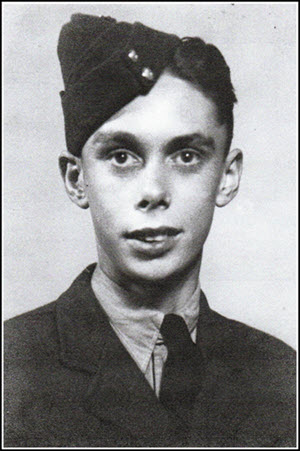

On 8th September 1941 I joined No. 1116 Squadron Air Training Corps which was based in Battle School, Reading, and in September 1942 I was granted a Certificate of Proficiency for qualifying as a F/Mech (E) (Flight Mechanic Engines).

The 3rd April 1943 saw me registering under the Armed Services Act at the Reading Labour Exchange (in South Street), attending a Medical Board at St Giles’ Hall, Southampton Street, Reading two weeks later. I passed Grade 1A. On 30th July 1943 I received my call up papers for the RAF followed by my Certificate of Service from No. 1116 Squadron on 12th August.

I was told to report to the RAF volunteer reserve No. 6 Attestation Section in Edinburgh on 9th August 1943 between 9am and 12noon. Having missed this time slot after a 10 hour train journey I went to the YMCA to sleep the night there. The following morning I returned to the Attestation Section together with about a dozen other lads, where we were given a test in English and Maths. I then had an interview with a Warrant Officer and was told that I would be accepted to be trained as a Flight Mechanic Engines – my dream had come true!!

I was told to report to the RAF volunteer reserve No. 6 Attestation Section in Edinburgh on 9th August 1943 between 9am and 12noon. Having missed this time slot after a 10 hour train journey I went to the YMCA to sleep the night there. The following morning I returned to the Attestation Section together with about a dozen other lads, where we were given a test in English and Maths. I then had an interview with a Warrant Officer and was told that I would be accepted to be trained as a Flight Mechanic Engines – my dream had come true!!

We then had to fill in a lot of forms, and I was given my paybook. My number was 3021582 – a number I remember to this day so engrained is it in my memory. On pay days you stood to attention, answered your name by shouting “Sir” and your last three numbers, in my case “582”. Then we were taken to the station to catch a train to the RAF training camp at Padgate near Warrington, Lancashire.

I travelled overnight to Padgate with a chap called Christmas, and arrived at Padgate RAF Training Centre with little idea of what was to become our routine for the next ten weeks. Our ATC training was a part time occupation – this was now for real.

I was one member of an intake of raw recruits, completing induction forms, followed by a thorough medical examination. We were then issued with our uniforms, footwear, other clothing, bedding, drinking and eating utensils, allocated a bed and locker (about thirty of us sharing a Nissen hut), and introduced to the Sergeant instructor who was to become our “God and Mentor”. His word was law!!

We were not prepared for the degree of physical fitness we were expected to achieve. At the end of the ten week training course, I felt fitter than at any time in my life, either before or since. The foot drill, known as “square bashing” turned us into a well disciplined company acting on orders with split second timing for no-one dared to be out of step or sync. I did not mind the foot drill but the forced route marching with rifle and full pack was definitely not my “cup of tea”.

The passing-out parade at the end of the course was our pride and joy, for we felt we had achieved something. I hope our Sergeant instructor felt the same way!

On completion of the basic training course we were split into groups, according to the technical trades for which we were classified – engines, airframes, wireless/radar, and so on. In my case, I was down to become a Flight Mechanic Engines, known as FME, to be trained at the Squires Gate Technical Training Centre Blackpool.

So at the end of October 1943, those of us who were earmarked as potential FMEs were transferred to Blackpool. After the usual arrival formalities we were billeted out, for the RAF had commandeered most of the local guest houses and boarding houses to accommodate the trainees. Each day we were bussed to and from the training centre.

We were at Blackpool for six months, and what a cold winter that turned out to be!! I still have vivid memories of having to do physical exercises on Blackpool sands in the middle of winter in just a vest and a pair of shorts with a bitter gale force wind blowing in off the sea taking the sand (and nearly us) into the town. It was quite exhilarating stuff – ears, eyes and mouth full of sand.

Our technical training was broadly based on learning the theory of the internal combustion engine, but in particular, the understanding of the Rolls Royce Merlin engine. We had to learn how to strip down the twelve cylinder engine, replace damaged parts, re-assemble and install the engine into the airframe. We were also taught the basics of metalworking and aero-dynamics.

By the end of April 1944, we had completed our technical training and passed our examinations, ready to be sent to operational airfields. We emerged as qualified FMEs, or so we thought, for little did we know then of the many technical problems to be faced in a bomber or fighter squadron on active service. We were soon to learn!!

I was drafted to be attached to No. 5o Squadron based at Skellingthorpe in Lincolnshire, a few miles to the west of Lincoln. This was to be my home, or place of abode, for the next two years.

Lincolnshire, being so flat and near the east coast, was the site for many bomber and fighter aircraft squadrons, bombers especially. Airfields were everywhere, or so it seemed. I never ceased to marvel how the aircraft found their way back to their own base after a ten hour mission, for from the sky one airfield must have looked just like another but such was the skill of the navigators and the science of radar, that they did just that.

Skellingthorpe airfield housed two squadrons, No. 50 and No. 61, both flying Lancaster bombers, each under the control of a Squadron Commander. The number of aircraft in each squadron varied according to the number of casualties from recent “trips” over enemy territory, for replacements could take some while to arrive. It was not unknown to receive a reconditioned aircraft with previous damage repaired which no one liked, especially the aircrew. We much preferred to receive a new replacement for obvious reasons.

We were each allocated to one particular flight of three or four aircraft but in practice we worked on one plane until it was lost in action; then transferred to another plane within the same flight.

Losses were very heavy particularly in the raids of 1943 and 1944 when the Ruhr centres were being bombed, and later when Berlin was targeted. The worst ordeal was to be on duty during the night of a raid, waiting for the planes to return, not knowing if your particular plane and crew would survive. Hearing them limp home, often on three engines and missing part of the plane or crew. A tour would consist of thirty raids; not many of the crews got through for you were lucky if you survived half a dozen trips. German night fighter aircraft, searchlights pinpointing you, anti aircraft gun fire, accidents, aircraft above you dropping their bombs onto you, mechanical failure, all contributed to a heavy loss rate. The rear gunners in particular had a short life span.

I have a photo, which I took, of Pilot Officer William F Dobson and crew, taken alongside of S for Sugar (on which I was a member of the ground crew) which went missing on the night of 3rd May 1944 whilst on a raid targeting a panzer division base at Mailly-le-Camp near Paris. They were actually the crew of V for Victor but their own aircraft was out of service on that particular night; such was the luck of the draw. Many times I wondered if they had survived as prisoners or war or whether they were killed, for at the time no-one knew what had happened. Years later, I discovered that they had crashed in flames into a field 2 km south west of Marigny-en-Orxois in the Department of Aisne – likely caused by the action of German night-fighters. Pilot Officer W F Dobson and Flight Engineer Sgt G R Williamson survived – were given shelter by the local inhabitants and smuggled back to England. The navigator Flt Sgt D R Jefferies also survived but was captured by the Germans and interned in Camp 16/357, PoW No. 3134. The other four members of the crew, Sgt George William Evans (Bomb Aimer) age 23; Sgt Ronald Russell (Air Gunner) age 23; Sgt John William Shaw (Air Gunner) age 19; and Sgt Fred Glover (Wireless Operator/Air Gunner) age 22 had all died.

The four who died are buried side by side in the Marigny-en-Orxois Communal Cemetery, near its northern corner. In October 2004, I wrote to the local Mayor and he kindly obtained for me a photograph of their grave, four memorials placed side by side surrounded by a low kerb. Unfortunately, I should have researched this much earlier, but sixty years afterwards has left it too late for me to visit the site. I can only remember their loss as a distant thought.

A strange thing but I do believe that the aircrew sensed whether or not they would survive each trip, and the feeling passed to us ground staff. When the aircrew turned up all on edge, inspected the plane much more than usual; then you knew they felt that they may not return. It was so often the case.

Our quarters were in Nissen huts on the edge of the airfield, each hut containing about twenty five men with a Corporal in charge. Shift working meant men coming and going all of the time so no one could afford to fall out with one’s neighbours in the adjoining beds; the spirit of comradeship was high – it had to be or it would never have worked in such a confined space. Each hut was heated with a central stove and woe betide the duty person who let the fire go out on a cold night!

Our working days were very much routine, governed by raids in the night and training flights during the day. The airworthiness of the aircraft was paramount, the welfare of the air crew very much in our hands, they had to trust us implicitly. Losses on raids were high enough without accidents caused by our failure to maintain the highest servicing standards.

We witnessed many tragedies; three in particular stand out in my mind. On 24th February 1945, a Lancaster in No. 61 Squadron QR-E (for Edward) returned from an aborted daylight raid on the Dortmund-Ems Canal still loaded with bombs. At 6.46pm as the aircraft was being de-armed there was a huge explosion killing three ground crew and injuring eleven others. Apparently some of the bombs aboard were fitted with time delayed detonators which the heavy return landing may have activated. A nearby Lancaster was damaged beyond repair.

On 19th May 1944, a worse explosion occurred when the driver of a tractor pulling several trailers of primed bombs on the perimeter road failed to notice that three 1,000 lb bombs had dislodged causing them to make contact with the road, and the whole lot went up leaving a large crater and little else. The tractor driver and one other airman were killed and substantial damage was caused to a nearby hangar. On another occasion I was standing outside our Nissen hut watching the.planes return from a raid when one of them came in much too high. My thoughts were – “he is going to overshoot” and he did! The next thing was a large explosion as he touched down beyond the end of the runway; the crew were all killed.

Life was not all doom and gloom. Our evenings off were often spent in Lincoln. There was always someone who could knock out some tunes on the piano to add to the merriment of beer drinking. The attitude of the aircrews in particular was, “we are here today and gone tomorrow,” and sadly, all too often that was so.

The years 1944/5 saw air bombing of Germany at its most intensive, often one thousand planes would take part in one night’s raid. We could only marvel at the central organisation directing these operations. One of the dangers during these very heavy raids, whilst over the target, was the possibility of being hit by the bombs of a plane flying above you or running into another plane in thick cloud formations. Such happenings occurred.

Opportunities for flying occurred now and again – I recall going on a low level strafing exercise coming in over the sea and the town of Skegness. That was exciting. On another occasion we had hydraulic failure and had to land on a special long runway somewhere up north built to accommodate aircraft with brake failure. We used every inch of that runway before coming to a halt!!

Bombing raids ceased in April 1945, much to everyone’s relief. During the war No. 50 Squadron completed the most overall sorties in Bomber Command and dropped the greatest tonnage of bombs (approx 21,000 tons). The squadron lost 1,002 aircrew and ground staff and 52 aircraft. During the eighteen months spent at Skellingthorpe I lost count of the number of night and day bombing raids we took part in, sometimes as many as five or six in a week, depending on the state of the weather.

Each aircraft had a crew of seven, very few of whom survived. There was only a one in three chance of a crew completing a tour of 30 operations over enemy territory. Shortly after the end of the War, several of us were taken on a trip to see from the air the bombing damage to the Ruhr Valley cities and towns area, that was an experience never to forget.

The conclusion of the war in Europe focussed our attention on the Far East for we were still at war with Japan. Rumours began to fly that we were going to be shipped to the island of Okinawa, but that came to nothing. In February 1946 I was drafted to RAF Metheringham Lincolnshire; a transit station. Then on 22nd February I was posted to Blackpool and billeted at a private residence. We were issued with tropical kit; shirts, shorts, etc. and told that we were going to Egypt. We left Blackpool on 1st March, arriving at Peacehaven Transit Camp on the south coast the following day.

Three days later we left Newhaven aboard SS Dinard, arriving at Dieppe. We left Dieppe on a train bound for Toulon and arrived in Neuvy-Pailloux. It was snowing hard, mud everywhere; and by mud I really mean mud – you could sink into it up to your knees. We were glad of a hot breakfast and a chance to wash and shave.

We passed through many stations and stops on our continued journey to Toulon, arriving there 6th March. We could see the blue of the Mediterranean in the distance. We stayed overnight and then boarded HMS Empire Battleaxe, and sailed for Egypt. I recall seeing a large number of French ships sunk or half submerged in the harbour waters, victims of our bombing raids.

We passed through many stations and stops on our continued journey to Toulon, arriving there 6th March. We could see the blue of the Mediterranean in the distance. We stayed overnight and then boarded HMS Empire Battleaxe, and sailed for Egypt. I recall seeing a large number of French ships sunk or half submerged in the harbour waters, victims of our bombing raids.

We arrived at the Port of Alexandria on 13th March. From there we travelled to RAF Heliopolis; a vast airfield and camp which was to become my base for the next eight months. We worked on Hercules engines for Wellington Bombers (French Air Force) as well as Oxford and Anson engines. We dressed in khaki shorts, short sleeved shirts, socks and shoes. It was often so hot that we worked with no shirts, which fifty years later has left me with the legacy of skin lesions much to my regret. Sunblock lotions were non-existent; we used olive oil, the worst possible thing; we really fried. We were housed in tents, plagued by flies and various bugs. I recall feeling pleased at finding a canvas bed in the store which was softer than the metal ones supplied, but in the middle of the night I realised why it had been thrown out of use, for masses of bugs came out from the folds of the canvas and enjoyed a feast on my body. I soon got rid of that bed.

Whilst there a few of us visited the Pyramids of Giza and the Sphinx, had the usual ride on a camel, and went inside the largest pyramid. The following day we had a trip down the Nile.

On 11th November, a number of us were posted to No. 37 Squadron at Shallufa in the Suez Canal area. Shallufa was a good airfield, very well organised; we had Lancaster bombers in No. 37 Squadron so we were at home working on the Rolls Royce Merlin engines once again.

The airfield itself was very isolated, nowhere to go outside of the perimeter fence. We had a number of German prisoners of war assisting us, but we had no problems. We occasionally had to do guard duty at a power station alongside the Sweetwater Canal which in turn ran close to the Suez Canal. If you fell into the Sweetwater Canal it was like falling into an open sewer, it was that filthy, and you had to have full treatment for rabies.

On 19th February 1946,after being transferred to Almaza, I heard that I was to be demobbed in March. We left on 3rd March for Cairo, then on a train to Kasfareet No. 21 Personal Transit Camp.

Once aboard Troop Ship Devonshire (18,000 tons), I was the sickest I have ever been, I have never seen such waves and rough seas, it was dreadful. They fed us with dried egg – I never want to see vomited egg again washing around on the decks and hammock sleeping quarters. We arrived at Liverpool on 20th March.

I have not mentioned the day to day routine in the year spent overseas, for they were ”just routine”, servicing aircraft engines, the occasional spell of sentry duty, and sipping the odd beer in the evening, but one statistic is interesting in that I saw 73 films in the various camp cinemas in that 363 days!!

From Liverpool we moved to 101 Personnel Dispersal Centre, Warton, Lancashire; where we had our final medicals, handed in our surplus air force clothing. Wish I had kept the forage cap and brass badge. For two days we went through the formality of completing our demobilisation papers and were given lectures preparing us for the return to civilian life.

Sunday 23rd March 1947 was my final day in the Royal Air Force. We were given our National Health and Employment Cards, drew 68 days leave wages, and received our Release and Service Books. We were issued with civilian clothes – suit, hat, raincoat, tie, shoes and socks. Then we boarded lorries, and were taken to Preston Station, where we said our farewells to each other. I caught the train and and arrived at Reading Station at 11.30pm. So ended a phase of my life; three years, seven and a half months; or one thousand, three hundred and twenty three days.

I am now 96 years of age but still proud of my period of time in the RAF. In spite of all the tragedy and horrors, it taught me independence, discipline, comradeship and character building which helped in my later career. It also gave me the chance of seeing something of life in other parts of the world.