The very first time I wrote for the Berkshire Family Historian, I described my first visit to Poland in the summer of 2016. This had happened by chance, after a business trip to Warsaw surprised me, and I appended a weekend before and three days after to explore the country of my ancestors. Despite an embarrassing lack of planning, not speaking a word of Polish and the perils of driving a rental car in Poland, I managed to tease out a lot of new information pertaining to my triple-great grandfather Wolf Jelen, in Zambrów and Śniadowo in the Łomża (pronounced Womja) district of northeastern Poland. I had visited archives, touched original records, found long-forgotten cemeteries hidden in forests and even attempted to communicate with non-English speaking locals, largely through the medium of mime and interpretive dance.

My only regrets were the shortness of the trip, and that given I had five Polish great grandparents, I had rather neglected my Shatkofsky (originally Szatkowski) family from Łask, near Łódź in the Piotrków district of central Poland and my Bercovitch (originally Berkowicz) family from Warsaw.

However, my abiding memory of my trip to Poland was that despite not speaking the language, it felt like I was finally home. I’ve lived in the United Kingdom and in California for most of my life, but have never felt grounded and always felt like an expat. In Poland, everything seemed to click. Maybe it was just because I desperately wanted to be in the land of my ancestors.

Imagine my excitement when it was announced that the 2018 IAJGS (International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies) Conference was to be in Eastern Europe for the first time, and in Warsaw in particular. I signed up immediately and took an extra week of vacation afterwards booking myself into hotels and hostels in Łask, Warsaw and Zambrów. The timing was mildly inconvenient, as I had been waiting for some surgery to repair a hernia operation that had gone wrong several years previously. I managed to delay the surgery by a few weeks when it came up right in the middle of the conference. Still, I was in no pain or discomfort, so what could possibly go wrong?

Before setting off to Poland, I conducted extensive research into the above families, trying to work out exactly what would benefit from some time in Poland away from the computer. In particular, the very wonderful https://jri-poland.org website (accessible from the JewishGen website) gave me a wealth of data indexing the Polish vital records, and sometimes easy access to the records themselves on the Polish State Archives (PSA) website, but occasionally the record would not be viewable and only a lengthy mail exchange in my best (non-existent, but generated from Google translate) Polish with the archives followed by painful delays attempting international money transfers of UK currency in the vast sums such as 50 UK pence per record, were necessary. This latter process could be bypassed by turning up at the archives themselves and asking (usually in English) to view the records stored there.

The conference was expected to be excellent and a very large contingent of JGSGB members had made the trip to Warsaw too, some not from the UK. One of my conference highlights was a fascinating presentation that suggested that even if tombstones had been desecrated and removed from Jewish cemeteries, planning permission for the memorials and tombstones may still exist in archives such as those in Łódź. I still need to investigate tombstone planning permission records.

I arrived on the Saturday before the conference and checked into my hotel, then immediately walked to the nearest Jewish cemetery on Okopowa street. This was a mile or two, but exercise is good for you and fear is a powerful motivator – I avoided complex negotiations with Polish taxi drivers who might not speak any English. Sadly, it being Shabbat [Sabbath], the cemetery was closed but I studied the various memorials outside and vowed to come back on Sunday, but then spent the rest of the day at POLIN, the Museum of Jewish History in Warsaw (which is a short walk from that cemetery), on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto. This enabled me to complete the tour of the museum at a more leisurely pace than my first attempt back in 2016 when hunger had got the better of me after 5 hours – it is exceptional, so leave plenty of time!

Having registered for the conference on Sunday morning, I went back to Okopowa Street cemetery – on foot, of course. In my previous trip to Poland I had visited this cemetery, but due to lack of research and planning I used the unsuccessful technique of wandering around aimlessly trying to trip over the tombstones of my ancestors in a cemetery with 200,000 graves. However this trip I was armed with grave locations and names from a Polish cemeteries index website (https://cemetery.jewish.org.pl/lang_en/), that also included photographs. Even so, I wanted to see the stones for myself.

Back then, I had been convinced that the Berkowicz patriarch – my great great grandfather, was Avraham (Abraham). I had discovered 6 different graves for Abraham Berkowicz and already had pictures from the website. Unfortunately in between my first and second visits to Poland, I had proved to myself that the real patriarch was Shmuel (Samuel) and that these were 6 completely unrelated Abrahams. But there were no Shmuel Berkowicz graves in the cemetery index, so I decided to visit the Abrahams anyway. I discovered that it was really hard to find the rows and grave numbers so I only really managed to find one of the six Abraham Berkowicz graves. Essentially you had to navigate by finding a recognizable name on a tombstone, finding its grave location from the index and then trying to reorient your search for the tombstone you were actually looking for. Okopowa Street is huge, and the dim distant corners have turned into forest with the requirement for lots of branch hopping and limboing coupled with crunching of undergrowth. Note for self: take a machete next time. Sadly, the light was failing and I was conscious that the cemetery was going to close shortly. I managed to bag Abraham #1, but the tombstone had toppled a lot more than when its picture for the index website was taken, and so my pictures were much inferior. In an attempt to find Abraham #2, I raced into the forest with an enthusiastic sense of purpose and hopped, skipped and jumped to try to locate the grave location. I twisted rather awkwardly, and then decided to give up as I felt mildly peculiar. As I walked back from the forest onto the path, I experienced the worst pain I have ever experienced in my life – my hernia had strangulated.

I am not a medical person, but essentially this is not good. The pain brought me to my knees. Somehow I made it out of the cemetery on my knees, before very slowly rising and managing to walk very slowly to the mall next door, much like as if I had slipped a disc or two. I will spare you the details of what happened in the bathroom there, but I am proud that my British reserve prevented me from decorating the pavements of the land of my ancestors. After 30 minutes or so of washing the sweat off my brow, I walked the two miles back to my hotel room doing the slow soft shoe shuffle. It was not quick, but my fear of speaking to a Polish taxi driver without being equipped with the word in Polish for either strangulate or hernia, kept me going. My genealogical research had prepared me with the words for birth, marriage and death, and in hindsight a clever combination of birth and death might have worked.

Back in my hotel room, a serious number of pain killers were consumed and a well-earned lie down taken. I managed to reduce my discomfort, by wearing a belt directly over my stomach, essentially keeping my entrails in the place where you and I like to store them. I suddenly realized that the first conference session was about to start and I needed to move to the Hilton hotel. Luckily by then, the pain killers were doing their job. I happened to mention to vice-Chairman Daniel Morgan-Thomas that although I was ready for JGSGB booth duty at the IAJGS “share fair”, that I had been taken ill and that I may need him to deputise for me. I also managed to have a very pleasant conversation with JGSGB Emeritus President Anthony Joseph. Anthony is a practicing GP and although I was a little economic with the truth about my medical emergency, for which I accept full responsibility, he advised me that I probably wouldn’t kill myself if I kept going with my IAJGS plans. Anthony had some special expertise here, because if I recall he too happened to be on the waiting list for some hernia surgery at the time.

So, I avoided the Polish A&E department and continued to self-medicate on pain killers for the rest of the week. I did ok, as when the pain increased I would stagger back to my hotel room for a lie down and pop a few pills. Once it decreased I would walk back to the Hilton and carry on with a genealogical talk, or schmooze with the very many friends and colleagues from the genealogical world I inhabit. I even managed to speak at the JGSGB session where we act as the United Kingdom Special Interest Group of JewishGen. In the end, I think I only missed a couple of conference sessions that I really wanted to attend, including 30 minutes of the keynote by Antony Polonsky, the famous historian and author of The Jews in Poland and Russia.

The conference finished on Friday and, despite not being religious, I decided to attend a Friday night service at Nożyk Synagogue on Twarda Street. This is the only synagogue that was in existence when my relatives lived in Warsaw and that had survived World War 2, although I have no evidence that they worshipped there. I do have evidence that they at least once visited a photographer on the same street, which I admit is circumstantial. At the service, I bumped into several JGSGB friends such as Harvey Kaplan and Naomi Leon, so clearly others at the conference had similar ideas to me to experience what our ancestors had.

By the end of the week I was feeling almost back to normal, with the exception of a few strange bulges under my conference T-shirt. I decided to continue with my extra week in Poland to visit my ancestral shtetlach [settlements].

I rented a car from Warsaw airport and then set off on my week of ancestral tourism. My first stop was Łask, some 2 hours south west of Warsaw, where my Szatkowski family were from. In summary, I discovered that my great, great grandmother Udla Kufert had not married three men, possibly simultaneously, and had my great grandfather Szymon Szatkowski with the third. Instead, she had two serial marriages and the Szatkowski name had been changed from Cudek or Sodek or Tzudek. I also discovered that Szymon’s wife Liba’s maiden name was Lipkowicz and not Pineras as written on my grandmother’s birth certificate.

The old Jewish cemetery in Łask was easy to find, especially having prepared using the Virtual Shtetl website for Łask (https://bit.ly/3Ks7aYI), available from the Town Finder on JewishGen, which pointed out all the sites of existing and former Jewish cemeteries, synagogues and other places of Jewish interest. I was looking for Szatkowskis, Lipkowiczes, Sodeks, Tzudeks or Cudeks. Sadly I found none. There was not a single standing tombstone and everything was deeply encased in moss. I tried to clean some but it was a near impossible task. In desperation I fell to my knees and cleared away the moss using leaves on one randomly chosen stone that looked in better condition than most. I could not believe it – I had found Abraham Berkowicz! The fact that he had never lived in Łask and that I had discovered that my relative was not Abraham anyway did not matter; it was still a good omen for the rest of my trip as I left the Łask cemetery chastened by Abraham from the terrible state of preservation.

I tried to visit the synagogue in Łask on the following day, Sunday. This was hard to find because it no longer exists. I walked around what is now a fire station, but the only hint of Judaism was a plaque in memory of the 3517 Łasker Jews that had been exterminated by the Nazis in August 1942. The rest of Łask was very Christian, but I was a wandering Jew in a strange land on a Sunday morning just after a church service had just spilled its worshippers into the town square. My final experience of the Łask area was a quick drive by of Szadkowice – a tiny village where I didn’t dare to get out – and Szadek, a small town where I admired old pictures of the town from its one pizzeria. This was because the Alexander Beider book of meanings of surnames of Poland had told me that Szadkowski means “from the town of Szadek or the village of Szadkowice”. On the way back to the hotel I took an obligatory selfie against a road sign for Szadkowska street, but Beider never mentioned that.

My Monday morning was spent in the Łódź archives. This was easy to find and quite different from my experience of Polish archives. I was not allowed to touch original record books and photograph them. Instead, I brought the records up on a screen, and photographed that. Some English was spoken by its helpful staff, but my request to download the pdf files of the records was met with blank stares. I left with an empty memory stick and a full camera. These records were different from the same records I had seen on Mormon microfilm at a FamilySearch centre, in that they were unikat records rather than duplikat. This distinction is similar to the difference between local registry office records and the General Registry Office equivalent in the UK. In one case, I spotted that the signatures were different as the unikat used a patronymic, allowing me to go back one more generation to my 4x great grandfather Jossel Sodek.

Monday afternoon was spent driving to the North East of Poland to Zambrów to repeat my first trip to the country in 2016. I stayed in the same hostel but this time didn’t lock myself out of my room. I went to the Jewish cemetery but this time found it immediately using Virtual Shtetl and the benefit of experience, rather than wandering around random fields and forests, and this time managed to avoid the mosquitoes. What a difference a couple of years makes! The cemetery had obviously been worked on by the Matzevah Foundation, a charity run by Dr. Steven Reece, and the stones had been reclaimed from the forest, cleaned and in some cases the letters had been painted to aid reading them. All in all a much happier experience than the bitter-sweet original when I came away sad that the forest had taken over the cemetery with no-one Jewish left in Poland to take care of it, but happy that the cemetery existed at all – unlike so many others.

Zambrów is in the Łomża district and so Tuesday allowed me to visit other cemeteries in Łomża, Jedwabne and Śniadowo. Łomża had two Jewish cemeteries that I could

find, guided again by Virtual Shtetl. The first was easy to find and had two areas on a hillside where there were some very old stones – more like boulders – with almost impossible to read Hebrew on them. At least they still existed. I didn’t really have any family from Łomża although some were from Piątnica, a mile or so away.

Hebrew inscriptions

The second Jewish cemetery had more traditional stones and looked fairly well preserved, especially as it was quite hard to get past several locked gates. In the end, I climbed a well-placed tree and dropped down into the cemetery without thought of my hernia nor how I was going to get out again.

The next couple of hours were spent productively photographing hundreds of stones. Even though these are unlikely to be my relatives, it felt important, because there is no guarantee that these stones will still be in place on my next visit, but I hope that they will. I managed to escape from the cemetery over a wall, avoiding anything pointy and metal, as I was saving myself for an English surgeon.

My next cemetery was in Jedwabne, the place I have written about before as being infamous for a 1941 atrocity where all of the Jews were rounded up, assembled in a barn which was set alight by Polish locals, encouraged by the Nazis. I again visited the memorial in the shape of a barn door set in concrete with a plaque containing an apology from Polish Pope Jean-Paul II. However, with the advantage of Virtual Shtetl I realised that I had missed a Jewish cemetery opposite the memorial. While I did find a memorial to the cemetery, rather than the atrocity, I struggled to find the cemetery itself, deciding not to wander too deep into the forest. I think there is still something to be found, and I will save that for my next Jedwabne visit.

fragments?

My final cemetery attempt was to be in Śniadowo, the town where my Jelen family came from before they moved to Zambrów. Although I had been guided by Virtual Shtetl, all I could find was a train line and an empty field, with ploughed fields bordering. It was peaceful to walk around for an hour or so, but I was saddened that there was not a single marker for the cemetery which might have been the final resting place of some of my Jelens, even if the Nazis had long ago stolen the tombstones for an important road building project. I did find some fragments of stones but the Hebrew on them was imaginary.

Wednesday saw me leave Zambrów to head back to Warsaw. Originally I had thought my Berkowiczes were from Warsaw, but as my research progressed I discovered records from Minsk Mazowiecki, Kałuszyn and Pruszków, all towns not far from the city. Szmul Berkowicz had married Szosia Gaier in Minsk M in 1885 and they were my 2x great grandparents. Szosia’s parents, my 3x great grandparents had married in Kałuszyn. I had managed to find a Polish passport from 1913 for Yitzchak Berkowicz, my great grandfather Gershon’s brother that stated he was from the Pruszków area of Warsaw. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a hotel in either Kałuszyn or Minsk M, so I settled for Pruszków.

Instead of starting my sightseeing in a cemetery, I wandered through the Kałuszyn town centre to get a feel for the place. Ironically, I found a Jewish tombstone embedded in the wall of a church. I hope that this is out of respect for its past Jewish community and not because they ran out of building materials. Hard to say. I quickly used Virtual Shtetl to guide me to the real Jewish cemetery outside of the town centre.

|

|

|

There I found a large memorial and a huge plaque put in place by the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland. It tells the story of how the Jews of Kałuszyn had been part of the community since 1714, contributing to the town as millers, wood and metal merchants as well as prayer shawl makers, and enjoyed the presence of great and scholarly Rabbis. However, in September 1939, 5200 Jews (some 60% of the population) were murdered. To top it off, all tombstones from the Jewish cemetery were stolen by the Nazis.

I wandered the empty fields for quite a while. Eventually, I came across one stone that might have been missed by the Nazis. I expect this is wishful thinking, but I live in hope. Maybe I saw some engravings on the corner of one side. Perhaps I wished too hard for it to be Hebrew. Back at the memorial, I left a couple of stones for me and for my other Berkowicz relatives who are descendants of these Kałuszyn ancestors and read the Kaddish [a hymn praising God].

On the following day, the Thursday, I visited Pruszków cemetery. After an hour of casing the joint, I could not figure out how to get in – there was no information on signs or notices. I even tried ringing doorbells of houses nearby to ask [for] some advice, but no-one answered. In the end, I launched myself over a 5 foot wall and dropped into the cemetery. This was the slightly better option compared to risking impalement on an 8 foot gate. However, at that point I had no idea how I was going to get out. The rationale was, I have come so far to visit – what could possibly go wrong?

It was worth the risk, because there were some beautiful tombstones, and even some Berkowiczes, although none whose given names were familiar. Most stones had been cleaned and painted, again the work of the Matzevah Foundation, I believe.

I managed to break out of the cemetery by climbing up a bricked in window, which enabled me to stand on the metal points of the 8ft gate, before dropping down to safety. There must be an easier way!

I discovered that Pruszków was very close to Góra Kalwaria, which I was familiar with as I had done some research for another JGSGB member with family from there. So I drove to Góra Kalwaria and again found myself outside a locked cemetery. After circling it for a while, I discovered that the local youth had prised the metal bars upwards to leave a narrow gap at the bottom of one side of the perimeter. However, I had a premonition of getting half way through and getting my hernia wedged. Instead, I found a sign with a phone number and called to be let in. It did cost me $20 (the Polish cemetery keeper would only accept dollars) but he opened the gate – which happened to be peppered with Nazi bullet holes from another atrocity – and also the door to the prayer hall inside. I even got to meet a Polish gentleman who was living in Israel and showed me some tombstones of his family. Luckily he spoke some English as my Hebrew is almost as bad as my Polish. For a change, I walked through the gate to leave this cemetery, happy that my premonition did not come to pass.

My next cemetery trip was to Minsk Mazowiecki on the Friday. I had visited earlier in the week, but it was getting late and I felt that I had not done it justice. In the cold light of day I managed to walk into this cemetery, which was very impressive. There are many standing stones in a good state of preservation. There is also a distinctive memorial. Sadly, I didn’t find any Berkowicz tombstones, but this was not too much of a surprise as I had failed to find any in the cemeteries database mentioned above.

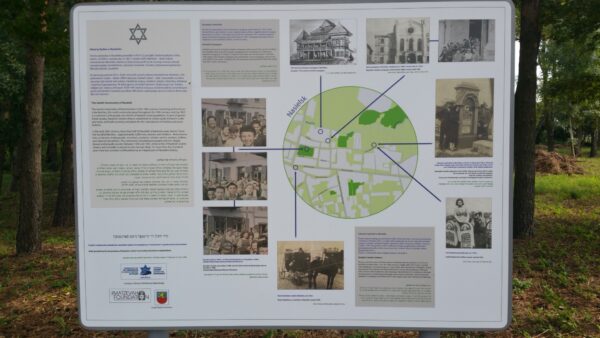

My final cemetery visit, on the Saturday of my flight home, was to Nasielsk. This is in the Warsaw area, but about an hour’s drive north of the city. I had been so inspired by Glenn Kurtz and his book at the conference that I thought it deserved a visit. I have no family from Nasielsk.

Although there are no tombstones left at the Nasielsk cemetery, its exact location is known and is being preserved by Jewish people whose family was from there, as well as with local support. Also, there are information boards telling people about the lost Jewish community, based on findings from Glenn Kurtz’s book, giving the history of Jewish Nasielsk. The tree lined avenues share a cemetery’s peacefulness.

When I returned to England I had my surgery as scheduled and have had no problems since. I don’t think the surgeon was terribly impressed by what he found and putting it right took much longer than anticipated.

Perhaps it was not the smartest course of action to climb trees, scale walls, shinny up windows to clamber over sharp metal pointed gates. So I cannot recommend or condone what I did. Please do not follow my bad example, even though I would do it again. Sometimes, you just have to go with your gut…

Leigh Dworkin is the current Chairman of the JGSGB. He has been researching his mainly Polish family for the last thirty-five years, but also tries to research into Lithuania and Belarus, from where his surname originates. He regularly presents at JGSGB Regional Groups, Special Interest Groups and conferences.