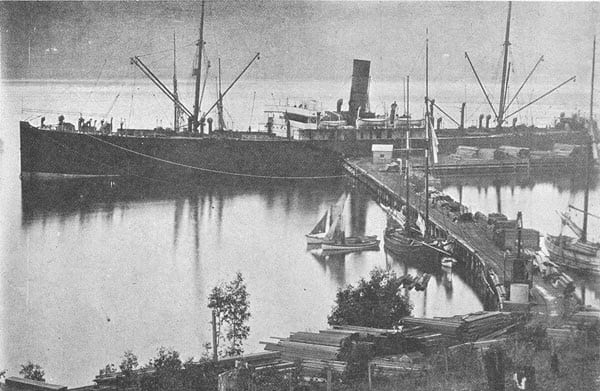

In 1914 Britain had a maritime empire. Goods, people, materials and ideas moved by sea. Nearly 2/3 of the food and drink consumed in Britain came from abroad. This global maritime supply network – that fed and fuelled civilian and military populations – was key to the First World War.

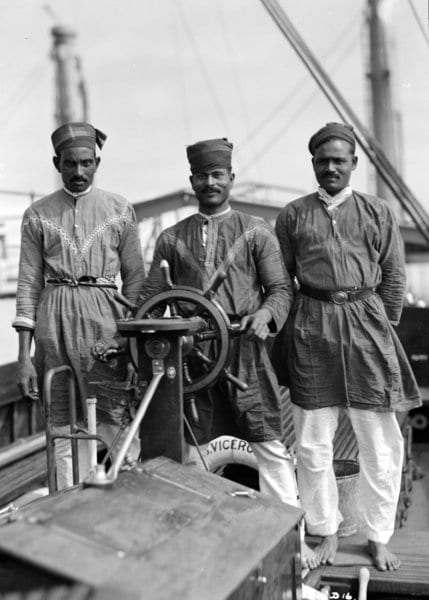

The crews of the ships that connected the empire were international. 30% of British merchant mariners were ‘foreign’. 17.5% were classed as ‘lascars’ (of Asian or Arab origin). That is 1 in 6 or about 51,000 men. Chinese, Arab, Asian, African and West Indian seamen were recruited in colonial ports like Aden, Lagos, Kingston, Cape Town, Bombay, Singapore and Hong Kong and from black and Asian sailor communities in British ports including London, Glasgow, Liverpool, Barry, Cardiff, Hull and Southampton.

Yet the stories we tell of the First World War often focus on soldiers in the trenches, naval battles and the sacrifices of white, British men.

The Marine Archaeology Trust’s ‘Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War’ project investigates the 1,000+ wartime wrecks along England’s south coast and focuses on the little known but vital struggle that took place on a daily basis just off our shores. Among the stories these wrecks tell are those of their crews – and of the black and Asian seamen who risked, and often lost, their lives on those ships.

These are not always comfortable stories. Many of these men were British colonial subjects, like the white seamen from Canada, New Zealand or Australia, but they were paid less (1/3 to 1/5 of the wage of men on standard or ‘European’ contracts), received fewer rations and smaller living quarters. Their conditions and rates of pay provided lucrative savings for the private shipping companies that made up the ‘British merchant marine’.

Racist ideas about supposed physical attributes determined a seaman’s role on a ship. Many black and Muslim seamen worked in the engine rooms or ‘stokeholds’ – dangerous and physically exhausting work in hot and noisy conditions. Hindu Asian and Chinese seamen frequently worked in galleys and on passenger liners it was Catholic, Portuguese-Asian men (often from Goa) who were stewards and in roles requiring interaction with white officers or passengers.

Casualties and deaths among black and Asian seamen were disproportionately high, in part because they worked in the most dangerous places. Ships sank fast and it was hard to reach lifeboats from below decks. A direct hit on an engine room was likely to be fatal.

These men had not joined the Navy but risked their lives anyway. Most had little choice. Many had lost their land as a result of imperial expansion and an imperial racial hierarchy, based on European ideas about race which emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, governed their working lives. In 1916-1917 there was a crisis in British shipping in Bombay when thousands of Indian seamen, including c.4000 Punjabis, took safer jobs with the British Mesopotamian labour corps. But new colonial regulations and coercion rather than better conditions forced them back to sea.

Black and Asian seamen do not appear on the 1928 Mercantile Marine War Memorial at Tower Hill, London. Instead, they appear on other Commonwealth memorials in Mumbai, Hong Kong or Suez. Historian John Siblon suggests that the Imperial War Graves Commission separated seamen so that only white British and European sailors would be commemorated in London. The memorials of the seamen

who died on the SS Aparima certainly reflects this suggestion. Of the 56 who died, 54 were British colonial subjects. The 24 white New Zealanders are all listed at Tower Hill, but the 29 Indians are recorded in Mumbai and the Chinese second carpenter in Hong Kong.

This post-war practice reflects some of the reasons why stories of black and 8Asian seamen are not often told in histories of the First World War. The records through which their lives are traced were written by colonial administrators and shipping companies for particular commercial and political purposes. Names were anglicised. Identities were blurred and memorials whitewashed.

First World War histories are also histories of empire and race. They are not always comfortable, but they are British histories – black, Asian and British histories.

You can find more information on black and Asian seamen in the First World War, including a free booklet, on the project website http://forgottenwrecks.maritimearchaeologytrust.org/lascars