February 6th 2018 marked the 100th anniversary of the passing of The Representation of the People Act, which extended the vote to all men over the age of 21 and to those aged 19 and above in the armed forces. However, more significantly, it gave the franchise to women, specifically those who were aged over 30 and who met the £5 property qualification. This newly enfranchised population voted for the first time a month after the Armistice on Saturday 14th December 1918. It was a key moment for women’s suffrage and one that had been anticipated and continually debated in Reading as elsewhere for over 50 years.

In 1866 1500 signatures were collected for the first mass women’s suffrage petition and the lone signatory from Berkshire was a Mrs Eliza Ratcliffe, Principal of the Burlton House Ladies’ School in Castle Hill, Reading1. John Stuart Mill, MP, presented the petition to Parliament and proposed an amendment to extend the franchise to all householders regardless of sex who met the qualification of the second Reform Act of 1867. Although defeated, support came from both sides of the house and from 1870 onwards bills in favour of women’s suffrage were presented on an almost annual basis2.

In 1872, the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS) organised a meeting at Reading Town Hall. Chaired by George Palmer, the hall was crowded with men and women. He argued the case for the extension of the franchise on the basis of equality and fairness, to him, a matter of common sense. He argued that the 1869 Municipal Franchise Act qualified 500 women to vote for town councillors, yet they were excluded from full suffrage. He ended by saying, “It could not be right to perpetuate injustice towards one half of the human race.3” The meeting agreed that the Chairman should sign a petition in favour of the current bill.

For many, however, it was a subject which challenged traditional thinking regarding the role of women in society, their intellectual abilities and aptitude for matters such as politics. At what appears to be the next major meeting in Reading in May 1878 headed ‘Taxation and Representation,’ indecision and uncertainty are evident. The chairman and Mayor, Mr J. Silver, made it clear that he did not entirely sympathise with the subject, but was reported as saying:

‘In common with everyone he never could oppose women’s rights. They could not be opposed. They had all the argument and sympathy as well as the persuasive power on their side. As to the question of the franchise, he would certainly prefer trusting himself to the quiet thoughtful vote of the women than to the excited balderdash emanating from beer and sawdust.’

Perhaps he could see both sides but could not quite relinquish the established way of doing things. George Palmer moved the first resolution stating:

‘…it was contrary to free and constitutional government that any number of persons should be deprived of representation in Parliament and that the suffrage should, therefore, be given to women.’

Interestingly, Palmer went on to say that enthusiasm in favour of women’s rights in Reading was lacking and further evidence to suggest that the cause still had some way to go came from the Rev. C. D. Du Port who said he had:

‘…asked two men above the average of culture and education to attend the meeting, one sent him a few lines of rhyme, and the other, a clergyman, said it was too good a joke for him to stand by him on such a platform in Lent.’4

In 1878 George Palmer was elected MP for Reading and, in his maiden speech in the Commons, he was in support of a private member’s bill to grant women the vote. He asked, ‘What is the best thing to be done in the interests of the country?’5 In his answer he cited the case of his mother, who with substantial lands and responsibilities, was disqualified from voting simply because she happened to be a woman.

At the old Town Hall in January 1887 Palmer was joined by Millicent Fawcett of the NSWS. After a short introduction by the chairman, the resolution was put forward that the Parliamentary Franchise should be extended to women who possessed the relevant qualifications and who, in matters of local government, had the vote.

During the 1895 general election, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett. Suffragists had no particular political allegiance, used legal and peaceful means to further the cause, continued with the introduction of Parliamentary bills and spread the word through meetings. However, frustrated by the ‘so near and yet so far’ results of the organisation, Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel, with others, established a breakaway group in 1903. The Women’s Social and Political Union or WSPU embraced a more militant approach to theelusive franchise and the suffragettes adopted the slogan ‘Deeds not Words’.

Until 1907, it is suggested, there was little in the way of a concerted following or presence of suffragists in Reading until the NUWSS formed a local group.6 They were followed in October 1908 by WSPU and Mrs Pankhurst was enthusiastically received at the time by an audience at a local meeting which included a number of men. The large amount of heckling and disturbance suggested many still held different views.

The first militant suffragette activity takes place in Reading in January 1908; a liberal party meeting was infiltrated by seven suffragettes who stood up at intervals and shouted, ‘Votes for Women’ or ‘What about the Women’. Their outbursts were met by calls of ‘chuck her out’ and they were physically removed from the meeting, one dropping on her way out a leaflet outlining ‘14 reasons for supporting women’s suffrage’.7

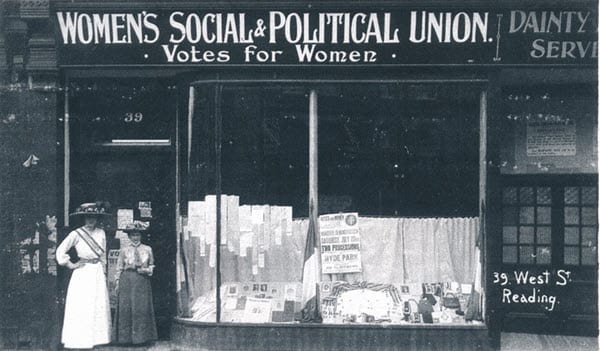

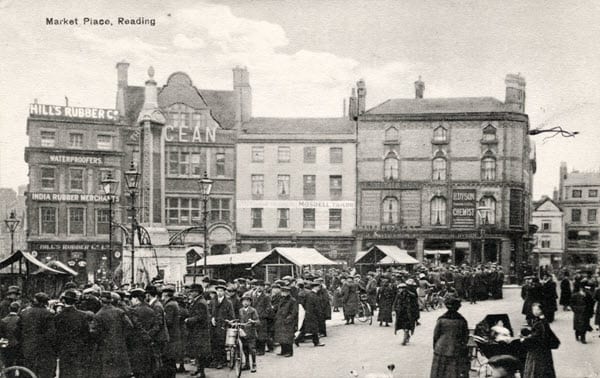

Both the NUWSS and WSPU opened shops in Reading selling suffrage literature. WSPU had shops at 39 West Street and 49 Market Place. The WSPU campaign in Reading, it is thought, focused on the women working at Huntley and Palmers and on a group of men who were in favour of women’s suffrage. The NUWSS had committee rooms at 154 King’s Road and a stall in the market arcade for literature.

On June 13th 1908 the NUWSS held a procession of 13,000 women to the Albert Hall and among their number were 70 members of the Reading Women’s Suffrage Society.

The Reading banner was followed by 50 to 60 members and amongst those heading the group was Councillor Edith Sutton. Teachers and nurses were among the dozen working women taking part, the female doctors joined the medical section of the March and one walked under the banner of the Primrose League.8 The Tilehurst group of the suffragettes held their first meeting in December 1908 and opinion was divided. One speaker said it was the view of the meeting that militant action was alienating people to the cause instead of winning them over, another stood and defended this approach as necessary if the issue were to be taken seriously.

In December 1909 there was a meeting of the Reading Branch of the National Anti-Suffrage League in the Palmer Hall, Admiral Fleet was in the chair. Mrs. Colquhoun was reported as saying:

‘that there would be danger to the State if the vote were given to women. It was necessary that they should have a clear idea of what the vote meant.’9

About this time David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, came to Reading to canvass for the liberal cause and to lend his support for their candidate Rufus Isaacs. At the tram sheds, Mill Lane, on January 1st 1910 a crowd of 6,000 gathered. Although precautions were taken to keep out likely troublemakers two canny suffragettes, Miss Streatfield and Miss Hudson, infiltrated the meeting. They were eventually discovered and ejected, but not before one of them shouted, in response to Lloyd George who was making a reference to robbery:

‘You’re a robber, because you take the women’s money and don’t give them the vote.’10

As Lloyd George left the meeting Kenneth Duke Scott of Hurst Nurseries, Twyford, seized him by the collar and refused to let him pass. Scott was a notable supporter of women’s suffrage and acted on behalf of the women. Order restored, a note was given to one of the newspaper representatives, which said:

‘Don’t you think you’re a miserable hypocrite to reject as you do the just claim of women for enfranchisement?’11

Later Scott defaced his copy of the 1911 census return form, refusing to give the names of the female members of his household.

A suffragette demonstration on July 15th 1910 at the corner of Station Road used the statue of King Edward VII as a podium and to display the WSPU banner. That the large crowd listened to the speakers showed a level of interest in their controversial demands. Mrs Pankhurst herself was in Reading later in the year when she addressed a meeting in the large Town Hall. Others on the platform were Miss Edith Morley, Dr Esther Carling and Mr Carling. A resident of Caversham, Mable Norton, took action and was sentenced to seven days in Holloway for her part in a demonstration. In her account she said:

‘I wasn’t a bit hysterical when I took a small hammer and smashed five windows one after the other. I did it quietly and deliberately. Then walked down the street to the police station cheered by a friendly crowd.’12

In March 1914 at least two church services were interrupted in Reading when a suffragette stood up to offer a prayer for Mrs Pankhurst who was once again in prison. On both occasions the women were allowed to proceed, showing perhaps a certain level of tolerance, but this was before the fire at Wargrave Church and the threats made to St Mary’s in the Butts.

Whether it was the outbreak of war that saved St Mary’s from such a fate we shall never know, but it was war that proved the catalyst for women’s suffrage. The issue continued to be debated during the war years, but the militancy stopped as many women focussed their energies on the Home Front. In taking on the jobs of men and by using their skills and abilities on all fronts to aid the war effort, they converted even their most ardent opponents. In 1918 the Reading electorate had increased to 45,379, but now it included 18,305 women.

1 https://www.parliament.uk/1866

2 A further nine Reading-based women added their names to the universal suffrage petition of 1869. https://livingreading.co.uk/news/suffragettes-in-reading

3 Berkshire Chronicle, December 7th 1872

4 Berkshire Chronicle, May 4th 1878 This article is the source for all of the quotes from this meeting.

5 Corley, T.A.B., Quaker Enterprise in Biscuits Huntley and Palmers of Reading 1822-1972 (London, 1972) p. 117

6 https://livingreading.co.uk/news/suffragettes-in-reading

7 Berkshire Chronicle, Jan 25th 1908

8 https://www.readingmuseum.org.uk/blog/five-reading-citizens-and-fight-for-votes-for-women

9 Reading Standard, December 11th 1909

10 Reading Standard, January 8th 1910

11 Reading Standard, January 8th 1910

12 https://www.readingmuseum.org.uk/blog/five-reading-citizens-and-fight-for-votes-for-women