Maria Giles was born in 1814, the daughter of a local labourer, William Giles of Northcroft Lane, Newbury, and his wife Mary.

She was christened Ann Maria in 1814 in St Nicolas, Newbury, but was generally known as Maria. By 1841 she was an unmarried dressmaker in The City, Newbury with two small children, Samuel and Clarissa. In August 1846 in St Nicolas Church she married Alfred Giles, possibly a relation. They then moved to one of the closes off Bartholomew Street. Her many and various misdeeds were reported in great detail in the local papers, as she was regularly in trouble with the law, not only for the crimes that led to her notoriety as a “cunning woman”, but also for assault, fraud and perjury.

Her first recorded misdemeanour was in August 1841. She had abandoned her two small children to be chargeable to the parish. She was described as being 5 feet 4 inches tall, of a dark complexion. Evidently she did return, as the next year a charge was brought against her of robbery from an “old man” of 65, John Crouch. He claimed she had robbed him of 2s while at The Pheasant beer house.

Other charges of assault and perjury followed. Maria did in fact have a day job, as well as her “cunning” activities. She is described from 1851 onwards as a midwife. She was not a particularly caring midwife, unfortunately, as this work also brought her back into court on a few occasions. In 1853 she attended the inquest of a baby who could have lived if it had had medical attention, but Maria, who said she would call a doctor, did not do so “in consequence of having been called elsewhere”. She was also charged with disposing of the body of another baby as stillborn, and once with child murder. Maria claimed this baby had been stillborn, terribly deformed, and that she carried it under her cloak to Newtown Road cemetery.

But these cases were not what brought Maria to the attention of first the local area, then nationally.

“Few cunning folk had as many brushes with the law as Maria Giles. Between 1853-1871 she appeared in court no less than eleven times, though not always as a defendant.”2

She was already known in 1847 as a “cunning woman” with the first reported mention of this title. In this context “cunning” comes from the Anglo-Saxon “cunnan”, to know, or to possess more knowledge than those around them, acquired either from a supernatural source, or an innate or hereditary ability.2

In 1847 the Berkshire Chronicle reported that a “woman called Benskin” repeatedly applied to a cunning woman (Maria Giles) to tell her fortune. Maria foretold that the young woman would receive £10 from her uncle in London. When no money arrived, another sovereign for a charm was demanded, which told the girl that the uncle needed a housekeeper. After travelling to London the girl found her uncle had a wife and no need for a housekeeper.

A whole series of similar cases followed over the years, usually where Maria claimed to be able to recover lost or stolen property, or, more cruelly, missing or deceased family members, by means of magic. By 1871 she had spent nearly five of the last eighteen years in prison, charged variously with obtaining money under false pretences, or under the witchcraft and vagrancy laws. Her second husband, William Tranter, was occasionally a co-defendant.

Her victims:

1849: John Thorn, an old blind man of Hoe Benham, asked her to find him a wife. A neighbour agreed to marry him, but together she and Maria robbed him of most of the money he trustingly handed over.

1853: Thomas Price, described as a poor carter boy of Peasemore, asked for her help in recovering stolen clothing. He paid £2 8s.

1856: Maria claimed to be able to cure Lucy Gunter’s “bewitched” husband, Joseph Gunter, of Aldermaston. She charged £3 16s 4 1/2d for her services. Claiming he was “double bewitched” Maria requested an extra £3.

1857: George Hibberd of Marlborough had lost a silver watch and handed over £3 18s in total to Maria.

1864: Maria claimed to be able to bring back “over hedges and ditches” Mary Ann Fisher’s errant husband, Henry Fisher of East Woodhay.

She also claimed she could raise Amey Siney’s mother from the grave in order for Amey, of Welford, to inherit her mother’s money.

To the judge’s regret, Maria, who had been charged with being a rogue and a vagabond, was freed on a legal technicality.

1868: Isaac Rivers, a labourer of Hampstead Norris, handed over several sums of money ranging from 2s 6d to 25s in order to recover a silver watch which eventually turned up in a farmyard.

1871: Hannah Long of Pamber had lost a pair of watertight boots, ¼ lb. tea, and ½ lb. sugar from her cart.

Emma Gregory, also of Pamber, had also lost goods from her cart.

These two cases led to Maria’s longest term of imprisonment yet: five years with hard labour.

How did Maria trick these people?

Each method she used demanded money in advance. When, naturally, there was no success, various excuses were given and more money was demanded.

One method was to claim that she had procured “chemicals” which she turned into drops. These were then sprinkled over, for example, the front door of the victim’s house.

The second method, used for recovering stolen property, was to use a glass and ask the aggrieved person to look into it. The face of the thief should be visible.

Another method was to whisper incantations to a book covered in cloth. The lost articles would then appear in the front of the victim’s house the next day.

When it came to curing the “bewitched”, Maria used a variety of household ingredients, such as cream and butter, which were thrown around the house and sprinkled on the doorstep.

How was Maria viewed locally?

She certainly quarrelled with her neighbours. She was evicted once, but always returned from prison to Bartholomew Street. Her notoriety may have even worked in her favour by spreading her reputation.

Mary Ann Pearce, a friend and neighbour, was a willing collaborator to get money from John Thorn by agreeing to marry him.

Mary Ann Fisher was immediately taken to Maria’s house after she came to Newbury in tears from East Woodhay and asked if anyone could tell her of a person who could “tell with a few words with the cards to get her husband back again”.

Emma Gregory was told in Aldermaston to “enquire a little way down Bartholomew Street”.

George Hibberd came from Marlborough, having heard of her reputation. Maria used the chemical trick on him and was not deterred by the distance between Newbury and Marlborough. She just requested a further 10s to render “everything right by return of post”.

Maria’s victims themselves were not immune from criticism from judges and the newspapers, particularly Isaac Rivers of Hampstead Norris, who was described by the judge as

“one of those credulous and absurd persons whose ignorance and superstition was so great that it really might be doubtful whether the law could protect him at all”.

Hannah Long was censured by the judge:

“If Mrs Long had not been drunk she would not have lost her things”.

The girl “Benskin” was described by the newspapers as a “silly noodle”.

Victims from Tadley came in for particularly harsh criticism from the Newbury Weekly News:

“the fact might be accounted for that the parties came from Tadley, and they were unaccustomed to look for anything intellectual from that quarter”.

Maria’s character

Was she an uneducated, callous villain, or was she a clever manipulator doing her best to help people? Opinions differed.

Against:

In 1864 in the case of Mary Ann Fisher, the judge summed up as follows: “You possess a heart that has no compassion. You took from that poor woman not merely every farthing that she possessed but the very garment she was wearing at the time. She was your victim and you showed no mercy.”

For:

Surprisingly, Maria did attract positive comments, and even defenders.

In 1868 the judge in the Isaac Rivers case addressed Maria in these terms:

“You have sent me a letter extremely well written and well expressed, evidently showing an amount of education that makes one deeply regret you should pervert that education to the shocking purpose you have done.”

However, he concluded:

“But you seem to prefer a course of crime.”

In 1871 Charles Slocock, a banker and magistrate of Donnington, petitioned the Home Office on the grounds that her most recent sentence (five years with hard labour) was unreasonably severe. It was turned down on the grounds that she had been sentenced before on seven previous occasions, that there was little hope of reformation, and that it was necessary to prevent the credulous from being victimised by her.

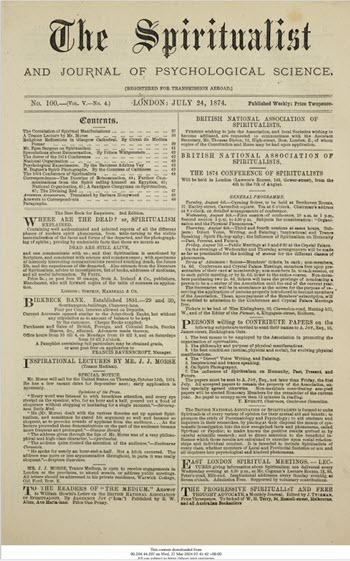

In 1872 the Newbury Weekly News printed a letter from Samuel Guppy of Highbury, North London which had recently appeared in the Spiritualist and which painted a touching, if unrecognisable, picture of Maria.

“This woman is 58 years of age. Five years penal servitude lands her at 63 – if she lives so long – broken in health and fit only for the poor house. In fact it is an imprisonment with hard labour for life. It appears that, although the good inhabitants of Newbury considered that telling fortunes or suggesting how stolen goods might be recovered, was verynaughty, they did not desist from tempting this poor woman… But it so happened that this woman was a most estimable woman, decent, orderly, not given to drink, always willing to attend even poor persons and never deterred by their ailments being contagious. She was in fact a universal favourite. She robbed no-one. She molested no-one.”

Maria’s family

Of her three brothers one, possibly two, died in infancy. Her sister Caroline married a bargee and lived nearby in the yards off Bartholomew Street. James Pottinger, Caroline’s first husband, once gave evidence on Maria’s behalf.

Maria’s first husband, Alfred Giles, died in 1865 and was buried in Newtown Road Cemetery. She then married a widower, William Tranter, in 1869. William Tranter died in horrific circumstances in 1877 when a pit on Wash Common, where he was digging out sand, collapsed in on him. At the inquest the jury presented their fees to the grieving widow. He was buried in Newtown Road Cemetery.

Of Maria’s two children, the older, Samuel Giles, joined the Army, then moved back to Newbury where he worked as a bricklayer. He married firstly in 1865 his stepsister, Annie Tranter, William Tranter’s daughter by his first wife.

The couple moved to Hammersmith, then Samuel returned to Newbury where he married his second wife Mary Ann Preston in 1883. They moved to Eastbourne with their daughter Violet, and Samuel died there in 1918.

Maria’s daughter, Clarissa Giles, was described as half-witted in 1853 when she was assaulted by a neighbour. She was admitted to the Berkshire County Asylum in 1870 and died there in 1875.

Maria’s stepson, William Tranter, met a violent end. His body, shockingly mutilated, was discovered in Potters Bar Tunnel on the Great Northern Railway in 1889. Maria attended the inquest. She described the man as her son by a former husband, although he was actually her stepson.

Maria’s last appearance in court was in 1891 when she gave evidence in an affiliation order case. She was recognised by the lawyer and asked if she had not made the acquaintance of the court before as a fortune teller. Maria refused to answer. The lawyer persisted.

“But don’t you practise the black arts? Don’t you bring them over hedges and ditches?”

Maria’s quick wit did not desert her. Amidst laughter she replied,

“Well, I didn’t bring this child over hedges and ditches.”

By this time Maria had married her third husband, John Mills, a labourer, in 1878. They continued to live in the City in Newbury until 1891 when they were living in Kennet Road. John died in 1892 and was buried in Newtown Road. Three husbands and her sister Caroline were buried there, but no record of Maria’s death or burial has been located with any certainty, and one wonders if Newbury’s last witch disappeared in a puff of green smoke.

References:

- Berkshire Chronicle, the Reading Mercury, and from 1867 the Newbury Weekly News, various dates.

- Davies, Owen. Popular magic: cunning folk in English history. Hambledon Continuum, 2007.